Events

| Name | organizer | Where |

|---|---|---|

| MBCC “Doing Business with Mongolia seminar and Christmas Receptiom” Dec 10. 2025 London UK | MBCCI | London UK Goodman LLC |

NEWS

Steppe Gold building Mongolia's premier precious metals group and progressing ATO mine expansion plans www.proactiveinvestors.com

Steppe Gold Ltd (TSX:STGO, OTCQX:STPGF) announced that it has entered into an arrangement agreement to acquire all of the issued and outstanding common shares of Anacortes Mining Corp.

The Mongolia-focused precious metals company said Anacortes shareholders will receive 0.4532 of a Steppe Gold common share for each Anacortes share held, which represents consideration of about C$0.48 per Anacortes common share.

“We are very pleased to add one of the highest-grade undeveloped oxide gold deposits in the world to our development pipeline,” Steppe Gold CEO Bataa Tumur-Ochir said in a statement.

“Our vision is to build a 200,000 ounce gold equivalent production profile, with our ATO Phase 2 expansion project expected to come online in 2025 and the Tres Cruces Mine moving to production soon thereafter,” Tumur-Ochir added.

About the company

Steppe Gold Ltd is Mongolia's premier precious metals company producing gold from the operational oxide zone of the ATO Gold Mine.

The company has completed a feasibility study into expansion of the ATO Gold Mine to approximately 100,000 ounces of gold per annum from the development of underlying fresh rock ores.

Press Interview on Mongolian Foreign Minister Battsetseg’s Working Visit to the PRC www.montsame.mn

Minister of Foreign Affairs of Mongolia Batmunkhiin Battsetseg paid a working visit to China on May 1-2, 2023 at the invitation of a member of the State Council and Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China Qin Gang.

-Foreign Minister, how would you define the purpose and the significance of your visit to the PRC?

-One of the priority goals of our Government is to intensify cooperation in all sectors and at all levels, and bolster our comprehensive strategic partnership after the pandemic with one of Mongolia’s two neighbors, the PRC. The PRC has defined their new development goals and appointed a new generation of leaders at the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in October, 2022, and its “Two Sessions” in March, 2023. The purpose of my visit was to promote bilateral relations and cooperation, and establish working relations with the PRC’s new generation of leaders. During my working visit to Beijing on May 1-2, I met and held official talks with PRC State Councilor and Foreign Minister Qin Gang, and exchanged views on a wide range of issues regarding Mongolia-China relations, and reached concrete agreements, which asserted to the importance of the visit.

It is important to maintain high-level mutual visits and meetings between our two countries, and both sides have been able to organize and maintain a frequency of such exchanges even during the difficult period of the pandemic.

One of the outcomes of my visit was that the two sides agreed to organize Prime Minister L.Oyun-Erdene’s official visit to the PRC in the near future.

-What were the concrete issues that were agreed?

-President of Mongolia Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh paid a state visit to the PRC in November 2022, during which he met with President Xi Jinping. Both sides reached an agreement at the highest level on issues such as promoting and developing bilateral relations and cooperation in the new era. In order to significantly contribute to the nation’s development we are mainly focusing on putting these agreements into action.

One of the priorities of Mongolia’s foreign policy is to develop friendly relations with our two neighbors. China too attaches great importance to its relations and cooperation with Mongolia and considers Mongolia as its good neighbor, good friend and good partner. In this regard, the parties agreed to bolster political trust, mutually respect the fundamental interests of each other, and develop an ideal example of bilateral cooperation in the region.

The key area of Mongolia-China relations is cooperation in the field of trade, economy and investment. The goal is to increase trade between the two countries to USD 20 billion by 2027. Our bilateral trade reached 13.6 billion USD 2022, and USD 3.48 billion in the first quarter of this year.

During the meetings with the Chinese side issues such as increasing port capacity, and intensifying the works of connecting them by road and rail, which would facilitate the increase of trade volume were raised. For instance, outstanding issues such as revising the 1955 Railway Agreement, 2004 Agreement on Border Ports and their Regime, 2014 Agreement on Transit Transport, and adding Khangi-Mandal railway port into the Agreement on Border Ports, and accelerating the construction work of the railway at the Gashuunsukhait-Gantsmod border port were addressed.

-Since the beginning of this year, China began to ease the strict travel restrictions imposed during the pandemic and people have begun to travel again. The Government of Mongolia declared years 2023 through 2025 the "Years to Visit Mongolia.” Was there any discussion and talks made on receiving tourists from China to Mongolia?

-In order for people to obtain positive and accurate information and understanding of each other’s cultures, histories and livelihoods, we should encourage our people to travel and visit each other’s countries. The two sides have discussed and agreed to organize Mongolian-Chinese culture and tourism forum, to upgrade and improve the e-visa process for tourists, to increase the number of direct flights and to make promotional materials on Mongolia available in Chinese in order to further promote tourism between the two countries. The land and air travel between the two countries have resumed to normal. The international passenger trains will resume its operation starting this month. Moreover, the Embassy of Mongolia to the People’s Republic of China opened a new “Culture Center” this year, which aims to promote Mongolia in China, organizing many events and activities promoting Mongolia, especially to the children and youth.

-Spring season is the time of the year when the yellow sandstorms start in Beijing. Nowadays, environmental cooperation is increasingly becoming one of the most important topics to be discussed among countries within the bilateral cooperation framework. Have you discussed this issue with the Chinese counterparts? What is the current progress of other development cooperation projects?

-Under the “One Billion Trees” National Campaign initiated by the President of Mongolia, a joint project to establish a “Research Center to Combat Desertification” is being implemented. China has an extensive experience in combating desertification and re-forestation efforts and therefore, has agreed to implement the abovementioned joint-project. Mongolia will be organizing the 17th Conference of the Parties (COP17) of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) in 2026 and China has agreed to cooperate with us in this regard as well.

The grants and concessional loans provided by the Government of the People’s Republic of China, significantly contribute in resolving pressing socio-economic issues in Mongolia. For instance, projects such as “Central Wastewater Treatment Plant of Ulaanbaatar City,” “Erdeneburen Hydropower Plant,” and “Underground Passageway” (which aims to reduce the Ulaanbaatar city traffic congestion) are being successfully implemented. In addition, the implementation of the joint-projects such as the “Grand Theatre of National Arts” and the “Presidential Sports and Training Center for Children and Youth,” which have been agreed upon during the President of Mongolia Mr. U. Khurelsukh’s state visit to People’s Republic of China, will commence this month.

-The PRC has become an active player on the international stage, and Chinese President Xi Jinping has announced three major initiatives: Global Security Initiative, Global Development Initiative, and Global Civilization Initiative. Does Mongolia support these initiatives?

-PRC President Xi Jinping proposed Global Development Initiative in 2019, the Global Security Initiative in 2022, and Global Civilization Initiative in 2023. These initiatives declare safeguarding humankind’s secure and peaceful life, sustainable development, diversity of civilizations, and promoting international cooperation in this regard as their primary objective. These are in line with our country’s foreign policy objectives and principles, and we are ready to exchange views and cooperate with the Chinese side in this direction.

Mongolia joined the Group of Friends to “Foster Global Development – Promote Stronger, Greener and Healthier Global Development for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” established by the PRC last year at the UN.

During the “Dialogue with World Political Parties High-level Meeting” organized on March 15, PRC President Xi Jinping proposed the “Global Civilization Initiative,” stating, “We advocate the respect for the diversity of civilizations. Countries need to uphold the principles of equality, mutual learning, dialogue, and tolerance. Countries need to keep an open mind in appreciating the perceptions of values by different civilizations and refrain from imposing their own values or models on others and from stoking ideological confrontation. Countries need to fully harness the relevance of their histories and cultures to the present times and push for creative transformation and innovative development of their fine traditional cultures.” These statements are consistent, in essence, with Mongolia’s foreign relations, policy, and objectives concerning cultural and humanitarian issues.

-The value of civilization includes religious issues. These issues are also relevant to Mongolia-China relations. What is our official position on this matter?

-Religion is definitely a core value of culture. Mongolia and China are both Asian Buddhist countries. There have been cases in world history where religious issues have affected relations between countries. Our two countries have a comprehensive strategic partnership, and we have been able to reach a mutual understanding and resolve any conflicts through dialogue.

Our citizens’ right to freedom of religion and expression is ensured and protected by law. Moreover, the state and religion shall conduct their activities separately and not interfere in each other’s affairs as stipulated in the Constitution of Mongolia.

I would also like to emphasize that religious issues are subject to the internal affairs of both countries. Mongolia conducts its policies and activities on any religious issues independently and without external interference, as it should. We will independently resolve any religious matters, including identifying the head of traditional Buddhist in Mongolia, without any involvement from outside.

Nowadays, we have ample opportunity to train its lamas internally and enhance their capacities. This undoubtedly will help us pursue independent religious policy and develop Buddhism in Mongolia on our own.

-During the visit were issues related to international relations discussed?

-Apart from issues of bilateral relations and cooperation, regional and international topics of mutual interests were also discussed. Within the framework of intensifying Mongolia-Russia-China trilateral cooperation, both sides agreed to renew the central railway corridor, accelerate the construction of the natural gas pipeline from Russia to China through Mongolia’s territory, and the construction of the Altanbulag-Zamiin-Uud highway project.

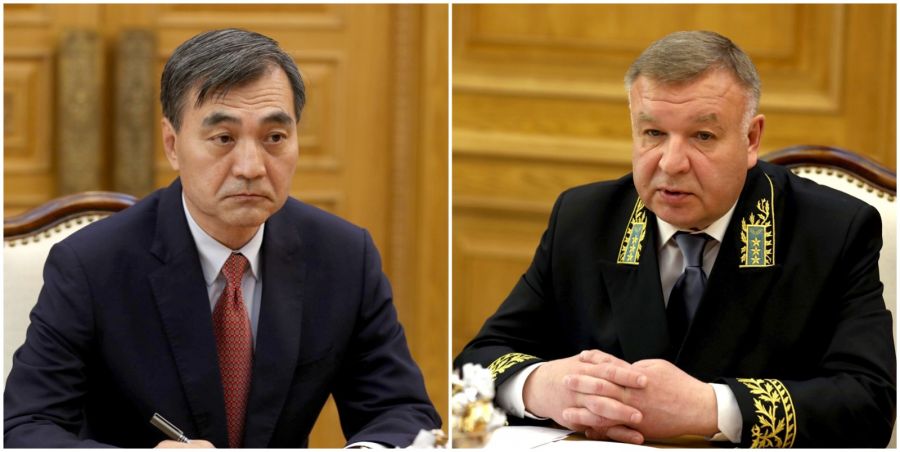

Prime Minister Receives Chinese and Russian Ambassadors www.montsame.mn

Prime Minister L. Oyun-Erdene received Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the People’s Republic of China Chai Wenrui and exchanged views on bilateral relations and cooperation on May 8.

During the meeting, the parties discussed preparatory work for Prime Minister’s visit to China, improving the infrastructure of border ports of the two countries, intensifying the railway connection process, and cooperation in the tourism sector.

On the same day, the Prime Minister received Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Russian Federation to Mongolia Yevsikov Alexei Nikolaevich, congratulated him on his new assignment, and wished him success in his future endeavors.

Cooperating in border ports and the energy sector and implementing large and joint projects, specifically, investing in “Ulaanbaatar Railway” Mongolia-Russia Joint Venture Company to improve its performance were the main issues of the meeting.

All High-Ranking Officials to be Prohibited from Participation in Government Procurement Activities www.montsame.mn

The Prime Minister of Mongolia, L. Oyun-Erdene, presented the draft amendment to the Law on Regulation of Public and Private Interests and Prevention of Conflict of Interest in Public Service and addressed the Parliament session on May 4. We present the summarized transcript of his speech for your perusal.

As we gather today, we are reminded of our historical responsibility to rebuild trust in government and by protecting the reputation of the fundamental pillars of democratic governance - the legislative, executive, and judiciary powers. It is our duty to put an end to the mistakes and corruption of the past 30 years, to respect the interests of the people, to truly fulfill the right of citizen representation, and to usher in a new era of ethical leadership for the next 30 years.

We, as members of State Great Khural, belong to the people, and we must lead by example. Ethical, disciplined, and responsible leadership should begin with us, in this hall. If we cannot hold ourselves to the highest standards, how can we ask government officials and citizens to strictly follow the adopted laws and regulations?

The Government of Mongolia has declared 2023 as the "Year of Fighting Corruption". This includes exposing corruption crimes through “whistleblow” operation, wiping “parasites” from public offices through “wipe-out” operation, and bringing back overseas escapers through "WASP" operation. The "5W" program has also been implemented to "transfer" illegal funds hidden in offshore areas and foreign countries to ensure the transparency of Government institutions.

It is clear that the giant oak tree of systemic corruption, which have been rooted deep into the soil, will not collapse in the blink of an eye. Those who benefit from corruption will do everything in their power to protect their interests, by using false information and creating an organized system to protect against theft. We must be vigilant and persevere in the fight against corruption.

As information becomes more transparent and citizens become more informed, the corruption system will continue to crumble. We must do what is right, and the truth will prevail. This is the advantage of Democratic Government.

Under the framework of the New Revival Policy, an anti-corruption legal reform has been launched and during this spring session, we will discuss and approve the Law on the Legal Status of Whistleblowers, the Law on Judiciary, and the National Anti-Corruption Program and amendments to the Constitution, the Law on Regulation of Public and Private Interests in Public Service and the Prevention of Conflict of Interest, and the Code of Conduct for Civil Servants.

Today, the draft amendment to the Law on Regulation of Public and Private Interests in Public Service and Prevention of Conflict of Interest, have been submitted to the State Great Khural.

Upon the passage of this law, all high-ranking government officials including President of Mongolia, Speaker of the State Great Khural, Prime Minister of Mongolia, members of the Parliament and Government, Governors of aimags and the capital city, as well as their spouses, cohabitants, children and any related party will be prohibited from participating in any form of procurement activities funded by the government, state-owned companies, and international organizations' projects and programs, jointly implemented by the government during their tenure in office. Furthermore, they will be precluded from receiving any concessional loans, grants, or guarantees during their tenure in office, as the draft law stipulates.

In addition to the officials mentioned above, the prohibition clauses apply to chairperson of political party which holds seats in the State Great Khural, members of the Constitutional Court, the Chief of Justice and judges of the Supreme Court, the State Prosecutor General, members of the Civil Service Council, as well as heads and deputies of organizations that report to the Parliament and the Government, including the Bank of Mongolia, the General Election Committee, and the Anti-Corruption Agency, the Central Intelligence Agency, National Police Department, Customs General Administration, National Emergency Management Agency, General Department of Taxation. Other agencies covered by the law include General Authority of State Registration, General Authority for Social Insurance, the Civil Aviation Authority and the Mineral Resources Authority.

By passing this law, we will establish clear boundaries between politics and business, marking the point of an ethical boundary where the state and business operate detachedly. I am confident that this law will serve to prevent and protect many politicians and civil servants from potential corruption risks in the future. Going forward, we will engage in active public discussion to implement basic reforms for making public service efficient and "doing more with less" by transforming the recruitment of civil service, transferring state property and workforce to the private sector, and introducing a unified system for civil servant salaries that is based on their productivity and results.

Thank you for your attention to this matter.

Shinhan Bank signs digital finance business agreement with Khan Bank of Mongolia www.korea.postsen.com

Shinhan Bank announced on the 8th that it has signed a strategic business agreement with Mongolia’s largest bank, Khan Bank, to promote digital finance.

Established in 1991, Khan Bank operates over 540 branches throughout Mongolia, and is the largest commercial bank in Mongolia, used by about 80% of Mongolia’s total population.

Recently, Khan Bank set ‘digital innovation’ as its strategic goal to promote digital-based banking innovation and chose Shinhan Bank as its benchmark.

Key executives and board of directors visited Shinhan Bank twice last year to experience various cases of digital innovation, including the futuristic store model ‘Digilog Branch’. Go’ was newly established in Mongolia.

Khan Bank then asked Shinhan Bank to share its know-how on overall digital finance, including △digital strategy △innovative service △ICT system.

Through this business agreement, the two companies plan to promote active collaboration in various fields, such as △sharing customer-centered digital innovation services and strategies △supporting organic customer experience design between online and offline channels △consulting on the establishment of innovative digital infrastructure linked to the financial system. made with

An official from Shinhan Bank said, “This business agreement with Khan Bank of Mongolia is significant in that Shinhan Bank’s differentiated digital financial services have been recognized not only in Korea but also abroad.” I will promote it,” he said.

Meanwhile, Shinhan Bank cooperated with Kiraboshi Financial Group in establishing a mobile specialized bank in 2022 by providing digital technology such as a non-face-to-face service model and a mobile banking app along with digital transformation consulting to Tokyo Kiraboshi Financial Group.

Ger areas around the Doloon Buudal, Chingeltei Avenue to be redeveloped www.gogo.mn

The meeting of the council of Governor of the capital city was held on May 4. At the meeting, the issue of determining the location, size, boundaries, and purpose of the project for redeveloping and building a new residential area in the 14th and 15th khoroos of Sukhbaatar district, or Doloon Buudal, was discussed.

The amendment of the Ulaanbaatar 2020 Master Plan and Development approach 2023 include the development of Ulaanbaatar into eight regions and 47 units. Selbe sub-center of the northern region belongs to the ninth unit. The sub-center was established to reduce over-concentration of the capital's population, increase the access to affordable housing, create healthy and safe working and living conditions for citizens, and reduce air, soil, and water pollution.

As part of the development of the Selbe sub-center, road, heat, electricity, communication, water supply, sewerage network, flood protection dam, landscaping, and green areas works were executed with soft loans from the Asian Development Bank. Currently, 162 hectares around Doloon Buudal have been proposed to be the location of the redevelopment and construction project. It includes 2082 units of the field.

The members of the council said that information should be transparent and citizens should be prevented from being harmed and exposed to fraud. The minutes of the council meeting was issued, and determining the location, size, boundaries, and purpose of the redevelopment and construction project of the ger areas will be discussed by the Citizens’ Reprensentative Khural.

Management, repairing and maintenance of the parking lot to be carried out through a public-private partnership

The report and conclusions of the task force responsible for planning, building, putting into economic circle and connecting to the integrated management system for vehicle parking lot in the territory of Ulaanbaatar city were presented.

In the last 10 years, Ulaanbaatar city’s population has increased by 1.2 times and the number of vehicles has doubled. According to a research, there are 15,181 vehicle parking lots in 344 locations within the Ikh Toiruu. Moreover, 28 vehicles that have been parked in public streets for a long time have been moved. Task force is working to consolidate the study of automatic closures throughout the capital and relevant decisions to be made. In addition, necessary information is being processed to connect authorized vehicle parking lots to the integrated system, and preparations are being made to select a contractor to improve parking lot management.

Mayor emphasized the need to enforce parking standards. Minutes were issued from the council meeting and task to study and present proposals for possible locations for paid parking on public roads and lots was given. In addition, the management, repair and maintenance of 1918 parking lots in 48 public locations will be organized by the private sector through open tendering within the framework of public-private partnership.

Citizens became able to monitor the process of issuing building permits

The Urban Development Agency has completely digitized the activities of the organization. Specifically, the "eBarilga" urban development digital system was put into operation last December in order to make information related to urban planning and construction permits available to citizens and the public, to increase citizens' participation in urban planning activities, and to quickly deliver government services. It is a combined web and mobile application system that all employees of the Urban Development Agency can connect to.

"eBarilga" digital system has the following advantages:

In 2022, more than 1,900 requests and complaints related to building and facility permits and violations were received by the department, most of which were requests to check information on building permits. By using the system, these applications and requests can be reduced by 30-40 percent, as well as the processing time.

Previously, citizens could only view and monitor the processing of requests sent online, but now it is possible to monitor the processing of paper-based requests using geoportals and mobile applications.

Citizens are able to see the future planning of their living environment, monitor urban development activities, vote and participate.

In addition, the meeting of the professional council to discuss urban planning issues is live streamed on the organization's website and YouTube page. In this way, citizens have the opportunity to openly receive the issues and information discussed at the meeting, and to monitor the activities of granting building permits. Minutes were issued from the meeting of the council, and the necessary funds were decided in connection with the above-mentioned works.

President Meets Students Studying in the UK under the “President’s Scholar-2100” www.montsame.mn

Over the course of the visit to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, President Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh met students who are studying in this country with the “President’s Scholar-2100” scholarship in London.

The “President’s Scholar–2100" scholarship program has been successfully implemented since 2021, awarding the best students from each of the 330 soums and the capital city to study at the world’s best universities. The scholarship qualifies students based on their academic achievements, engages them in the preparatory program to help them meet the qualifications of the world's best universities, and provides financial assistance during their studies abroad.

According to the regulation on Presidential Scholarship adopted by the Government, the students who have completed at least three years of study in their school's catchment area and have the highest average score in the General Entrance Examination in mathematics and foreign languages are eligible to participate in the “President’s Scholar–2100."

There are in total of 29 Mongolian students studying in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland under this scholarship, of which 15 students are studying at the University of Bristol, one of the Top 100 universities in the world.

Expressing his satisfaction with the successful implementation of the “President’s Scholar-2100” scholarship program, allowing youths to study at prestigious universities in foreign countries, the President reminded students to exert themselves in studying and hold high the name of Mongolia, always keeping in mind that they are representing their country.

During the meeting, students said they were happy to be awarded the "President's Scholar-2100" scholarship and shared their impressions and experiences on studying at the world’s top university. Besides the academic studies, students highlighted their personal developments and expressed that they would make use of the knowledge and experience gained while studying abroad to help in the development of Mongolia.

At the end of his speech, the President wished the students academic success and expressed his confidence that they would graduate as future leaders who will make a valuable contribution to the development of Mongolia, and become a bridge for relations and cooperation between the citizens of the two countries. Moreover, the President reaffirmed the special attention of the government to youths and their education and development.

Coronation concert: William says he is 'so proud' of his father King Charles www.bbc.com

The Prince of Wales has paid tribute to his "Pa" King Charles the day after the Coronation, saying the late Queen Elizabeth II would be "a proud mother".

Addressing the crowds at Windsor Castle for the Coronation concert, William said his grandmother was "up there, fondly keeping an eye on us".

He said this weekend was "so important" because it was all about service.

Highlighting King Charles' achievements over the last 50 years, William said: "Pa, we are all so proud of you."

And the heir to the throne made his own vow to the nation, saying: "I commit to serve you all. King, country and Commonwealth."

King Charles and Queen Camilla - colour-coordinated in blue, with the Queen in a royal blue jumpsuit - smiled and waved their own flags during the evening.

The Princess of Wales attended with her and William's oldest children, Prince George and Princess Charlotte. Prince Louis, who has just turned five, stayed at home after his busy day at the Coronation on Saturday.

The Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh were seated near the King and Queen, with Prime Minister Rishi Sunak behind them. Prince Andrew, Duke of York, and his ex-wife the Duchess of York, Sarah Ferguson, also attended, as did Zara Tindall and her husband Mike.

The crowd of 20,000 people got their tickets in a public ballot, with many more watching performances from stars including Katy Perry and Take That on BBC One and BBC Radio 2.

Host Hugh Bonneville - the Paddington and Downton Abbey actor - addressed the royal guests as the show began and acknowledged the King's love of the arts, joking he was "the artist formerly known as prince".

The concert featured musical acts including maestro Andrea Bocelli and Sir Bryn Terfel collaborating on You'll Never Walk Alone, and Olly Murs, who sang Dance with Me Tonight, while there were also spoken word pieces amidst the music.

Cold Feet actor James Nesbitt performed work by poet Daljit Nagra, while fashion designer Stella McCartney spoke about conservation.

There were video cameos from a range of stars, including British acting legend Joan Collins, former James Bond actor Pierce Brosnan, artist Tracey Emin and Welsh singer Tom Jones - all of them recounting little-known facts about the monarch.

And Top Gun actor Tom Cruise delivered a video message from his War Bird plane, saying: "Pilot to pilot. Your Majesty, you can be my wingman any time," before saluting and banking off.

The King seemed to enjoy a skit involving Bonneville and Muppet Show stars Kermit and Miss Piggy, in which Miss Piggy said "King Charlesy Warlesy" was expecting them in the royal box.

At the end of the show, Kermit was seen to have made it to the box, waving a flag in front of Prince Edward but there was no sign of Miss Piggy.

The Royal Shakespeare Company, Royal Ballet, Royal College of Art, Royal College of Music and the Royal Opera also took part in the show.

The royal patronages came together for the first time, with a one-off performance from Romeo and Juliet featuring actor Ncuti Gatwa - the new star of Doctor Who - and Olivier Award nominee Mei Mac.

Members of the Royal Family were seen dancing and singing along to Lionel Richie's All Night Long - with even the King getting to his feet, as did the Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh, Edward and Sophie, and Zara and Mike Tindall.

William's speech on stage came immediately after Richie's performance - with the prince referring to the US singer-songwriter's hit, saying: "I won't go on all night long", which drew a laugh from his father.

In his speech, William thanked everyone for making it "such a special evening" before turning to the significance of the weekend.

"As my grandmother said when she was crowned, coronations are a declaration of our hopes for the future," he said. "And I know she's up there, fondly keeping an eye on us. She would be a proud mother.

"For all that celebrations are magnificent, at the heart of the pageantry is a simple message. Service."

He said that after entering Westminster Abbey for Saturday's service, the first words spoken by his father were his pledge to continue to serve.

The prince praised the King for warning about damage to the environment "long before it was an everyday issue", and for his work with the Prince's Trust, the charity Charles set up which supports young people.

"Perhaps most importantly of all, my father has always understood that people of all faiths, all backgrounds, and all communities, deserve to be celebrated and supported," he said.

"Pa, we are all so proud of you."

The prince gave his thanks to those who serve "in the forces, in classrooms, hospital wards and local communities" before offering his own vow of service.

He finished by saying "God save the King", which was repeated loudly by the crowd before the national anthem was sung.

It was a tender and heartfelt message from William. There was an element of taking on the baton here too.

At last year's Platinum Jubilee concert it was Charles who as Prince of Wales gave thanks to his mother. Now it was William as Prince of Wales who gave the vote of thanks, stepping into the role of heir.

The stage, in Windsor Castle, resembled the union jack with catwalks jutting out from the centre creating multiple levels for the 70-piece orchestra and band.

Singer Paloma Faith sang as landmarks around the UK were lit up in celebration - including Blackpool Tower, Edinburgh Castle and Wales Millennium Centre in Cardiff.

And there was the first multi-location drone show to be staged in the UK, with 1,000 drones in formation: a Welsh dragon, spanning 140m, was seen in Cardiff, while a watering can was seen over the Eden Project in Cornwall.

Take That closed the show with Never Forget - with the choristers of St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, singing the song's introduction.

Mongolia to produce Bulgarian yoghurt with Lacto-bacteria www.news.mn

Mongolia is the second Asian country that will produce Bulgarian yoghurt with the bacterium Lactobacillus bulgaricus. An agreement on the use of the license was signed between the Bulgarian State-owned dairy producer LB Bulgaricum and one of the largest Mongolian food production companies – APU Company.

The initiative to enter the Asian market was taken by Caretaker Economy Minister Nikola Stoyanov and is being done with the active support of the Ambassador of Mongolia to Bulgaria S.Lkhagvarusen. The two were also present at the official signing of the document.

“Talks on this cooperation started in December of last year and in just four months we have managed to reach the signing of today’s agreement. It will allow authentic Bulgarian yoghurt to be sold in Mongolia,” said Minister Nikola Stoyanov. The Minister of Economy and the Mongolian Ambassador stressed that this is a step in the direction of strengthening bilateral economic relations between the two countries.

“Bulgaria is the homeland of yoghurt and we will use the national traditional technology for the production of dairy products in Mongolia,” the APU Company management said. On their part, it was emphasized that the agreement will allow them to fulfill one of the goals set by the Mongolian state to produce healthy and useful food. They have already visited the facility of LB Bulgaricum in Vidin (on the Danube) to get acquainted with the production process in the Bulgarian company. There is also interest in joint projects in research and development and the creation of joint products tailored to the Mongolian market.

The agreement has a term of five years. The Mongolian APU Company receives a license to develop, produce, sell and distribute dairy products with original Bulgarian starters for the territory of Mongolia, for which it will also pay licensing fees to LB Bulgaricum.

MSE to Cooperate with BSE www.montsame.mn

Management teams of the Mongolian Stock Exchange, a State-Owned Company and the Budapest Stock Exchange of Hungary held an online meeting and signed a Memorandum of Cooperation on May 3.

The MoC coverage is focused on the areas of:

Developing debt instruments, and equity and investment fund products;

Improving company governance;

Developing joint products and platforms.

- «

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

- 119

- 120

- 121

- 122

- 123

- 124

- 125

- 126

- 127

- 128

- 129

- 130

- 131

- 132

- 133

- 134

- 135

- 136

- 137

- 138

- 139

- 140

- 141

- 142

- 143

- 144

- 145

- 146

- 147

- 148

- 149

- 150

- 151

- 152

- 153

- 154

- 155

- 156

- 157

- 158

- 159

- 160

- 161

- 162

- 163

- 164

- 165

- 166

- 167

- 168

- 169

- 170

- 171

- 172

- 173

- 174

- 175

- 176

- 177

- 178

- 179

- 180

- 181

- 182

- 183

- 184

- 185

- 186

- 187

- 188

- 189

- 190

- 191

- 192

- 193

- 194

- 195

- 196

- 197

- 198

- 199

- 200

- 201

- 202

- 203

- 204

- 205

- 206

- 207

- 208

- 209

- 210

- 211

- 212

- 213

- 214

- 215

- 216

- 217

- 218

- 219

- 220

- 221

- 222

- 223

- 224

- 225

- 226

- 227

- 228

- 229

- 230

- 231

- 232

- 233

- 234

- 235

- 236

- 237

- 238

- 239

- 240

- 241

- 242

- 243

- 244

- 245

- 246

- 247

- 248

- 249

- 250

- 251

- 252

- 253

- 254

- 255

- 256

- 257

- 258

- 259

- 260

- 261

- 262

- 263

- 264

- 265

- 266

- 267

- 268

- 269

- 270

- 271

- 272

- 273

- 274

- 275

- 276

- 277

- 278

- 279

- 280

- 281

- 282

- 283

- 284

- 285

- 286

- 287

- 288

- 289

- 290

- 291

- 292

- 293

- 294

- 295

- 296

- 297

- 298

- 299

- 300

- 301

- 302

- 303

- 304

- 305

- 306

- 307

- 308

- 309

- 310

- 311

- 312

- 313

- 314

- 315

- 316

- 317

- 318

- 319

- 320

- 321

- 322

- 323

- 324

- 325

- 326

- 327

- 328

- 329

- 330

- 331

- 332

- 333

- 334

- 335

- 336

- 337

- 338

- 339

- 340

- 341

- 342

- 343

- 344

- 345

- 346

- 347

- 348

- 349

- 350

- 351

- 352

- 353

- 354

- 355

- 356

- 357

- 358

- 359

- 360

- 361

- 362

- 363

- 364

- 365

- 366

- 367

- 368

- 369

- 370

- 371

- 372

- 373

- 374

- 375

- 376

- 377

- 378

- 379

- 380

- 381

- 382

- 383

- 384

- 385

- 386

- 387

- 388

- 389

- 390

- 391

- 392

- 393

- 394

- 395

- 396

- 397

- 398

- 399

- 400

- 401

- 402

- 403

- 404

- 405

- 406

- 407

- 408

- 409

- 410

- 411

- 412

- 413

- 414

- 415

- 416

- 417

- 418

- 419

- 420

- 421

- 422

- 423

- 424

- 425

- 426

- 427

- 428

- 429

- 430

- 431

- 432

- 433

- 434

- 435

- 436

- 437

- 438

- 439

- 440

- 441

- 442

- 443

- 444

- 445

- 446

- 447

- 448

- 449

- 450

- 451

- 452

- 453

- 454

- 455

- 456

- 457

- 458

- 459

- 460

- 461

- 462

- 463

- 464

- 465

- 466

- 467

- 468

- 469

- 470

- 471

- 472

- 473

- 474

- 475

- 476

- 477

- 478

- 479

- 480

- 481

- 482

- 483

- 484

- 485

- 486

- 487

- 488

- 489

- 490

- 491

- 492

- 493

- 494

- 495

- 496

- 497

- 498

- 499

- 500

- 501

- 502

- 503

- 504

- 505

- 506

- 507

- 508

- 509

- 510

- 511

- 512

- 513

- 514

- 515

- 516

- 517

- 518

- 519

- 520

- 521

- 522

- 523

- 524

- 525

- 526

- 527

- 528

- 529

- 530

- 531

- 532

- 533

- 534

- 535

- 536

- 537

- 538

- 539

- 540

- 541

- 542

- 543

- 544

- 545

- 546

- 547

- 548

- 549

- 550

- 551

- 552

- 553

- 554

- 555

- 556

- 557

- 558

- 559

- 560

- 561

- 562

- 563

- 564

- 565

- 566

- 567

- 568

- 569

- 570

- 571

- 572

- 573

- 574

- 575

- 576

- 577

- 578

- 579

- 580

- 581

- 582

- 583

- 584

- 585

- 586

- 587

- 588

- 589

- 590

- 591

- 592

- 593

- 594

- 595

- 596

- 597

- 598

- 599

- 600

- 601

- 602

- 603

- 604

- 605

- 606

- 607

- 608

- 609

- 610

- 611

- 612

- 613

- 614

- 615

- 616

- 617

- 618

- 619

- 620

- 621

- 622

- 623

- 624

- 625

- 626

- 627

- 628

- 629

- 630

- 631

- 632

- 633

- 634

- 635

- 636

- 637

- 638

- 639

- 640

- 641

- 642

- 643

- 644

- 645

- 646

- 647

- 648

- 649

- 650

- 651

- 652

- 653

- 654

- 655

- 656

- 657

- 658

- 659

- 660

- 661

- 662

- 663

- 664

- 665

- 666

- 667

- 668

- 669

- 670

- 671

- 672

- 673

- 674

- 675

- 676

- 677

- 678

- 679

- 680

- 681

- 682

- 683

- 684

- 685

- 686

- 687

- 688

- 689

- 690

- 691

- 692

- 693

- 694

- 695

- 696

- 697

- 698

- 699

- 700

- 701

- 702

- 703

- 704

- 705

- 706

- 707

- 708

- 709

- 710

- 711

- 712

- 713

- 714

- 715

- 716

- 717

- 718

- 719

- 720

- 721

- 722

- 723

- 724

- 725

- 726

- 727

- 728

- 729

- 730

- 731

- 732

- 733

- 734

- 735

- 736

- 737

- 738

- 739

- 740

- 741

- 742

- 743

- 744

- 745

- 746

- 747

- 748

- 749

- 750

- 751

- 752

- 753

- 754

- 755

- 756

- 757

- 758

- 759

- 760

- 761

- 762

- 763

- 764

- 765

- 766

- 767

- 768

- 769

- 770

- 771

- 772

- 773

- 774

- 775

- 776

- 777

- 778

- 779

- 780

- 781

- 782

- 783

- 784

- 785

- 786

- 787

- 788

- 789

- 790

- 791

- 792

- 793

- 794

- 795

- 796

- 797

- 798

- 799

- 800

- 801

- 802

- 803

- 804

- 805

- 806

- 807

- 808

- 809

- 810

- 811

- 812

- 813

- 814

- 815

- 816

- 817

- 818

- 819

- 820

- 821

- 822

- 823

- 824

- 825

- 826

- 827

- 828

- 829

- 830

- 831

- 832

- 833

- 834

- 835

- 836

- 837

- 838

- 839

- 840

- 841

- 842

- 843

- 844

- 845

- 846

- 847

- 848

- 849

- 850

- 851

- 852

- 853

- 854

- 855

- 856

- 857

- 858

- 859

- 860

- 861

- 862

- 863

- 864

- 865

- 866

- 867

- 868

- 869

- 870

- 871

- 872

- 873

- 874

- 875

- 876

- 877

- 878

- 879

- 880

- 881

- 882

- 883

- 884

- 885

- 886

- 887

- 888

- 889

- 890

- 891

- 892

- 893

- 894

- 895

- 896

- 897

- 898

- 899

- 900

- 901

- 902

- 903

- 904

- 905

- 906

- 907

- 908

- 909

- 910

- 911

- 912

- 913

- 914

- 915

- 916

- 917

- 918

- 919

- 920

- 921

- 922

- 923

- 924

- 925

- 926

- 927

- 928

- 929

- 930

- 931

- 932

- 933

- 934

- 935

- 936

- 937

- 938

- 939

- 940

- 941

- 942

- 943

- 944

- 945

- 946

- 947

- 948

- 949

- 950

- 951

- 952

- 953

- 954

- 955

- 956

- 957

- 958

- 959

- 960

- 961

- 962

- 963

- 964

- 965

- 966

- 967

- 968

- 969

- 970

- 971

- 972

- 973

- 974

- 975

- 976

- 977

- 978

- 979

- 980

- 981

- 982

- 983

- 984

- 985

- 986

- 987

- 988

- 989

- 990

- 991

- 992

- 993

- 994

- 995

- 996

- 997

- 998

- 999

- 1000

- 1001

- 1002

- 1003

- 1004

- 1005

- 1006

- 1007

- 1008

- 1009

- 1010

- 1011

- 1012

- 1013

- 1014

- 1015

- 1016

- 1017

- 1018

- 1019

- 1020

- 1021

- 1022

- 1023

- 1024

- 1025

- 1026

- 1027

- 1028

- 1029

- 1030

- 1031

- 1032

- 1033

- 1034

- 1035

- 1036

- 1037

- 1038

- 1039

- 1040

- 1041

- 1042

- 1043

- 1044

- 1045

- 1046

- 1047

- 1048

- 1049

- 1050

- 1051

- 1052

- 1053

- 1054

- 1055

- 1056

- 1057

- 1058

- 1059

- 1060

- 1061

- 1062

- 1063

- 1064

- 1065

- 1066

- 1067

- 1068

- 1069

- 1070

- 1071

- 1072

- 1073

- 1074

- 1075

- 1076

- 1077

- 1078

- 1079

- 1080

- 1081

- 1082

- 1083

- 1084

- 1085

- 1086

- 1087

- 1088

- 1089

- 1090

- 1091

- 1092

- 1093

- 1094

- 1095

- 1096

- 1097

- 1098

- 1099

- 1100

- 1101

- 1102

- 1103

- 1104

- 1105

- 1106

- 1107

- 1108

- 1109

- 1110

- 1111

- 1112

- 1113

- 1114

- 1115

- 1116

- 1117

- 1118

- 1119

- 1120

- 1121

- 1122

- 1123

- 1124

- 1125

- 1126

- 1127

- 1128

- 1129

- 1130

- 1131

- 1132

- 1133

- 1134

- 1135

- 1136

- 1137

- 1138

- 1139

- 1140

- 1141

- 1142

- 1143

- 1144

- 1145

- 1146

- 1147

- 1148

- 1149

- 1150

- 1151

- 1152

- 1153

- 1154

- 1155

- 1156

- 1157

- 1158

- 1159

- 1160

- 1161

- 1162

- 1163

- 1164

- 1165

- 1166

- 1167

- 1168

- 1169

- 1170

- 1171

- 1172

- 1173

- 1174

- 1175

- 1176

- 1177

- 1178

- 1179

- 1180

- 1181

- 1182

- 1183

- 1184

- 1185

- 1186

- 1187

- 1188

- 1189

- 1190

- 1191

- 1192

- 1193

- 1194

- 1195

- 1196

- 1197

- 1198

- 1199

- 1200

- 1201

- 1202

- 1203

- 1204

- 1205

- 1206

- 1207

- 1208

- 1209

- 1210

- 1211

- 1212

- 1213

- 1214

- 1215

- 1216

- 1217

- 1218

- 1219

- 1220

- 1221

- 1222

- 1223

- 1224

- 1225

- 1226

- 1227

- 1228

- 1229

- 1230

- 1231

- 1232

- 1233

- 1234

- 1235

- 1236

- 1237

- 1238

- 1239

- 1240

- 1241

- 1242

- 1243

- 1244

- 1245

- 1246

- 1247

- 1248

- 1249

- 1250

- 1251

- 1252

- 1253

- 1254

- 1255

- 1256

- 1257

- 1258

- 1259

- 1260

- 1261

- 1262

- 1263

- 1264

- 1265

- 1266

- 1267

- 1268

- 1269

- 1270

- 1271

- 1272

- 1273

- 1274

- 1275

- 1276

- 1277

- 1278

- 1279

- 1280

- 1281

- 1282

- 1283

- 1284

- 1285

- 1286

- 1287

- 1288

- 1289

- 1290

- 1291

- 1292

- 1293

- 1294

- 1295

- 1296

- 1297

- 1298

- 1299

- 1300

- 1301

- 1302

- 1303

- 1304

- 1305

- 1306

- 1307

- 1308

- 1309

- 1310

- 1311

- 1312

- 1313

- 1314

- 1315

- 1316

- 1317

- 1318

- 1319

- 1320

- 1321

- 1322

- 1323

- 1324

- 1325

- 1326

- 1327

- 1328

- 1329

- 1330

- 1331

- 1332

- 1333

- 1334

- 1335

- 1336

- 1337

- 1338

- 1339

- 1340

- 1341

- 1342

- 1343

- 1344

- 1345

- 1346

- 1347

- 1348

- 1349

- 1350

- 1351

- 1352

- 1353

- 1354

- 1355

- 1356

- 1357

- 1358

- 1359

- 1360

- 1361

- 1362

- 1363

- 1364

- 1365

- 1366

- 1367

- 1368

- 1369

- 1370

- 1371

- 1372

- 1373

- 1374

- 1375

- 1376

- 1377

- 1378

- 1379

- 1380

- 1381

- 1382

- 1383

- 1384

- 1385

- 1386

- 1387

- 1388

- 1389

- 1390

- 1391

- 1392

- 1393

- 1394

- 1395

- 1396

- 1397

- 1398

- 1399

- 1400

- 1401

- 1402

- 1403

- 1404

- 1405

- 1406

- 1407

- 1408

- 1409

- 1410

- 1411

- 1412

- 1413

- 1414

- 1415

- 1416

- 1417

- 1418

- 1419

- 1420

- 1421

- 1422

- 1423

- 1424

- 1425

- 1426

- 1427

- 1428

- 1429

- 1430

- 1431

- 1432

- 1433

- 1434

- 1435

- 1436

- 1437

- 1438

- 1439

- 1440

- 1441

- 1442

- 1443

- 1444

- 1445

- 1446

- 1447

- 1448

- 1449

- 1450

- 1451

- 1452

- 1453

- 1454

- 1455

- 1456

- 1457

- 1458

- 1459

- 1460

- 1461

- 1462

- 1463

- 1464

- 1465

- 1466

- 1467

- 1468

- 1469

- 1470

- 1471

- 1472

- 1473

- 1474

- 1475

- 1476

- 1477

- 1478

- 1479

- 1480

- 1481

- 1482

- 1483

- 1484

- 1485

- 1486

- 1487

- 1488

- 1489

- 1490

- 1491

- 1492

- 1493

- 1494

- 1495

- 1496

- 1497

- 1498

- 1499

- 1500

- 1501

- 1502

- 1503

- 1504

- 1505

- 1506

- 1507

- 1508

- 1509

- 1510

- 1511

- 1512

- 1513

- 1514

- 1515

- 1516

- 1517

- 1518

- 1519

- 1520

- 1521

- 1522

- 1523

- 1524

- 1525

- 1526

- 1527

- 1528

- 1529

- 1530

- 1531

- 1532

- 1533

- 1534

- 1535

- 1536

- 1537

- 1538

- 1539

- 1540

- 1541

- 1542

- 1543

- 1544

- 1545

- 1546

- 1547

- 1548

- 1549

- 1550

- 1551

- 1552

- 1553

- 1554

- 1555

- 1556

- 1557

- 1558

- 1559

- 1560

- 1561

- 1562

- 1563

- 1564

- 1565

- 1566

- 1567

- 1568

- 1569

- 1570

- 1571

- 1572

- 1573

- 1574

- 1575

- 1576

- 1577

- 1578

- 1579

- 1580

- 1581

- 1582

- 1583

- 1584

- 1585

- 1586

- 1587

- 1588

- 1589

- 1590

- 1591

- 1592

- 1593

- 1594

- 1595

- 1596

- 1597

- 1598

- 1599

- 1600

- 1601

- 1602

- 1603

- 1604

- 1605

- 1606

- 1607

- 1608

- 1609

- 1610

- 1611

- 1612

- 1613

- 1614

- 1615

- 1616

- 1617

- 1618

- 1619

- 1620

- 1621

- 1622

- 1623

- 1624

- 1625

- 1626

- 1627

- 1628

- 1629

- 1630

- 1631

- 1632

- 1633

- 1634

- 1635

- 1636

- 1637

- 1638

- 1639

- 1640

- 1641

- 1642

- 1643

- 1644

- 1645

- 1646

- 1647

- 1648

- 1649

- 1650

- 1651

- 1652

- 1653

- 1654

- 1655

- 1656

- 1657

- 1658

- 1659

- 1660

- 1661

- 1662

- 1663

- 1664

- 1665

- 1666

- 1667

- 1668

- 1669

- 1670

- 1671

- 1672

- 1673

- 1674

- 1675

- 1676

- 1677

- 1678

- 1679

- 1680

- 1681

- 1682

- 1683

- 1684

- 1685

- 1686

- 1687

- 1688

- 1689

- 1690

- 1691

- 1692

- 1693

- 1694

- 1695

- 1696

- 1697

- 1698

- 1699

- 1700

- 1701

- 1702

- 1703

- 1704

- 1705

- 1706

- 1707

- 1708

- 1709

- 1710

- 1711

- 1712

- 1713

- 1714

- »