Events

| Name | organizer | Where |

|---|---|---|

| MBCC “Doing Business with Mongolia seminar and Christmas Receptiom” Dec 10. 2025 London UK | MBCCI | London UK Goodman LLC |

NEWS

Mongolia to Host UNCCD COP17 With Participation of 10,000 Delegates www.montsame.mn

The 17th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD COP17) will be held in Mongolia from August 17 to 28, 2026.

More than 10,000 delegates from over 190 countries are expected to attend the conference, where participants will discuss pressing global environmental challenges, including desertification, land degradation, drought, and pastureland management, as well as solutions to address these issues.

Hosting UNCCD COP17 in Mongolia will showcase the country’s active role in combating desertification and generate positive impacts for tourism and international cooperation. It will also provide opportunities to present Mongolia’s policies and management practices in environmental protection and climate change mitigation, while learning from the experiences of other countries. In addition, the conference will open doors to new investment and financial support for projects and programs focused on land and pasture management, as well as anti-desertification measures, thereby expanding international cooperation in the environmental sector.

The event will also create opportunities for the exchange of scientific knowledge, innovation, and the introduction of advanced technologies and best practices in Mongolia. At the same time, it will serve as a platform to promote the country’s history, culture, and traditions to international delegates, media representatives, and visitors, thereby contributing to the growth of the tourism, entertainment, and transportation sectors. Citizens will also be able to participate in volunteer, cultural, and social campaigns during the conference, creating temporary job opportunities.

CNN's Blueprint spotlights the innovators propelling Mongolia into a digital future www.cnn.com

For many, Mongolia is a destination to explore its vast wilderness and disconnect from the outside world. For Mongolians, however, connectivity is everything. With 3.5 million people and 5 million active phone numbers, digital life is thriving - especially in the capital, Ulaanbaatar. CNN'sBlueprint examines how the booming startup scene led by young Mongolian innovators is reshaping people's lives and driving solutions to pressing issues like pollution, congestion and climate change.

Among Mongolia's standout innovators is the team behind UBCab, a local ride-hailing startup tackling Ulaanbaatar's urban navigation challenges. By combining Google Maps data with custom input based on local landmarks and unofficial addresses, UBCab has developed a tailored mapping system that brings greater efficiency to the city's transportation network. Another local startup, Tapatrip, is a travel and transport platform designed to allow locals and tourists alike to explore Mongolia with greater convenience. With plans for global expansion, CEO Erdenechimeg Davaasuren hopes this will become Mongolia's first billion-dollar startup.

The surge in mobile connectivity also sets the stage for a new era of online commerce in Mongolia. Shoppy, launched in 2017 by Mendbayar Tseveen, integrates global marketplaces and serves as a ticketing platform for major events like the Playtime Music Festival. Another ecommerce platform, Stora, led by Enkhjin Otgonbayar, connects Mongolian consumers to products from Chinese and American marketplaces through its fully integrated logistics platform that optimises shipping lead times.

In addition to digital innovation, Mongolian entrepreneurs are also tackling climate change through sustainable infrastructure. Oyuka Munkhbat and Batmunkh Myagmardorj, co-founders of Airee, developed the country's first biodegradable wool air filters to address the issue of worsening indoor air pollution.

As well, efforts to build greener physical infrastructure are also gaining momentum. Mongolia now boasts its first LEED Platinum-certified building, featuring advanced insulation, solar panels, and energy-efficient HVAC systems. The building is home to IM Motors, where Gantulkhuur Bekhbat, CEO of MMS, is championing a vision of an energy-independent Mongolia, powered by sustainable infrastructure for electric vehicles.

Airtimes for 30-minute special:

Saturday, 20th September at 12:30pm HKT

Sunday, 21st September at 11am and 6pm HKT

Monday, 22nd September at 1:30am HKT

About CNN International

CNN's portfolio of news and information services is available in seven different languages across all major TV, digital and mobile platforms, reaching more than 379 million households around the globe. CNN International is the number one international TV news channel according to all major media surveys across Europe, the Middle East and Africa, the Asia Pacific region, and Latin America and has a US presence that includes CNNgo. CNN Digital is a leading network for online news, mobile news and social media. CNN is at the forefront of digital innovation and continues to invest heavily in expanding its digital global footprint, with a suite of award-winning digital properties and a range of strategic content partnerships, commercialised through a strong data-driven understanding of audience behaviours. CNN has won multiple prestigious awards around the world for its journalism. Around 1,000 hours of long-form series, documentaries and specials are produced every year by CNNI's non-news programming division. CNN has 36 editorial offices and more than 1,100 affiliates worldwide through CNN Newsource. CNN International is a Warner Bros. Discovery company.

What Is Driving Closer Japan-Mongolia Ties? www.thediplomat.mn

In July, Japan’s Emperor Naruhito and Empress Masako visited Mongolia in a trip wrought with symbolism. In East Asia’s geographical configuration, changes in the external and domestic environment are playing a role in Ulaanbaatar and Tokyo’s renewed partnership.

Emperor Naruhito’s state visit to Mongolia — the first by a Japanese emperor — was highly symbolic, reflecting both historical reconciliation and a new era of partnership. The visit came shortly before the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II – in which Mongolia and Japan fought on different sides – as well as the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which resulted in Japan’s surrender.

To Mongolia, this historical symbolism serves as a leading foreign policy tool. Ulaanbaatar has a strategic interest in having Japan as a third neighbor, as the relationship intertwines shared democratic values with economic and technological advantages.

In 2022, Mongolia and Japan upgraded their 2010 Strategic Partnership to a “Special Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity.” The upgrade promised greater cooperation not only in the East Asia region but also extending to the Indo-Pacific. The augmented partnership aimed to implement human-centered development with a 10-year plan from 2022-2031. Ulaanbaatar is most keen to see cooperation in areas like investment, infrastructure, renewable energy, and technology. As of 2023, Japan had invested over $1 billion in Mongolia.

In recent years, Japan has shown more interest in Mongolia’s critical minerals, especially, copper, fluorspar, and rare earths that can be utilized for Japan’s advanced manufacturing in robotics, automobiles, and semiconductors.

In addition, Japan has invested in renewable energy. The government of Mongolia partnered with the Asian Development Bank, the Japan Fund for Joint Credit Mechanism, and the Strategic Climate Fund in the Upscaling Renewable Energy Sector Project. “Upon successful completion,” the ADB description noted, the project will deliver “clean electricity to 70,000 households while annually avoiding 82,789 tons of carbon dioxide emission.”

The United States’ slashing of financial commitments – including in the clean energy sector after its withdrawal from the Paris Agreement – will force regional actors like Mongolia, Japan, and South Korea to cooperate regionally and rely on each other.

To Japan, Mongolia’s cooperation on food security is crucial. There is growing concern for ensuring long-term food security, and Japanese policymakers have been seeking alternatives sources. The Special Strategic Partnership between Mongolia and Japan thus includes cooperation on food security, regenerative agricultural practices, forestry and fisheries.

While bilateral cooperation between Mongolia and Japan is crucial for people-to-people relations and developmental projects, in East Asian security context, the Japan-Mongolia relationship certainly carries geopolitical connotations.

Since 2011, Mongolia’s third neighbor policy has enlarged Ulaanbaatar’s foreign policy sphere. This is to Tokyo’s advantage, as Mongolia’s third neighbor initiatives serve as an additional platform for Japan to conduct diplomacy. These mechanisms support trilateral partnerships between Mongolia, Japan, and the U.S. and help promote peaceful resolutions to protracted challenges concerning denuclearization of North Korea, and abduction issues. The annual Ulaanbaatar Dialogue on Northeast Asia is one example.

Another element in the renewed Japan-Mongolia partnership is the changing geopolitical paradigm in East Asia, including the changing U.S. policy toward its Asian allies. Although this may not have a direct impact on Japan-Mongolia relations, it will impact the potential of Japan-Mongolia-U.S. trilateral mechanisms.

The Trump administration’s tariffs and emphasis on burden sharing are clear indications of the shrinking U.S. direct presence in the region.

Japan recognizes this change and is responding to it by strengthening relations with other partners, including Mongolia. Regional stability is crucial for both countries’ security and economic development.

For Mongolian foreign policy, in addition to having strong ties with Russia and China, robust third neighbor bilateral and trilateral mechanisms are crucial. Given the rising geopolitical uncertainties and sharpening of strategic competition, Mongolia and Japan’s strengthened relationship is indeed timely. Despite the current transition in Japanese leadership, the two governments will continue to cooperate toward a more focused, people-to-people level of partnership.

Guest Author

Bolor Lkhaajav

Bolor Lkhaajav is a researcher specializing in Mongolia, China, Russia, Japan, East Asia, and the Americas. She holds an M.A. in Asia-Pacific Studies from the University of San Francisco.

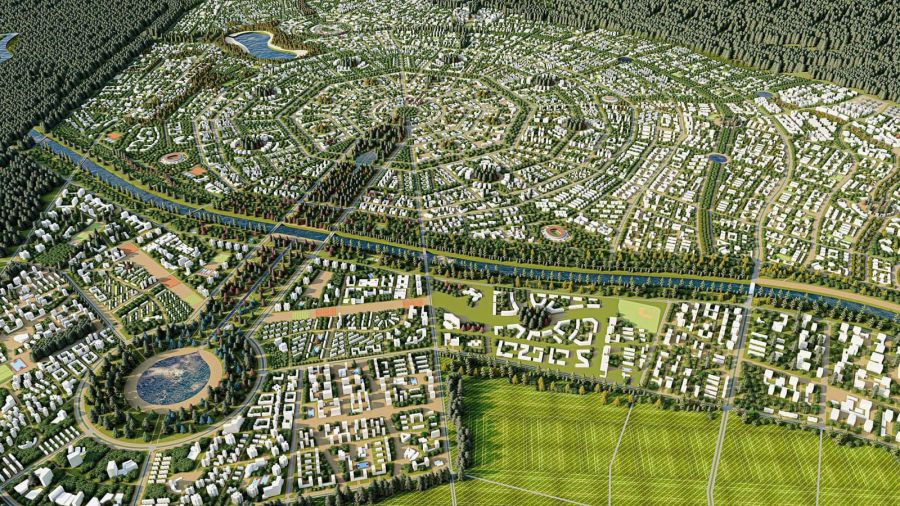

Infrastructure Construction Continues at Hunnu City www.montsame.mn

In line with the General Development Plan for Ulaanbaatar City until 2040, Hunnu City is planned on 31,000 hectares in Sergelen soum, Tuv aimag, to reduce Ulaanbaatar’s concentration and promote balanced regional development.

The city is expected to house 150,000 residents and create 80,000 jobs, and also plans to include universities, a student campus, government offices, transport and logistics hubs, and an economic free zone.

As of today, the infrastructure construction at Hunnu city has progressed as follows:

Power supply works: 86 percent

Water supply works: 80 percent

Flood protection channels: 75 percent

Telecommunications network: 65 percent

Sewerage system: 10 percent

Heating supply: 10 percent

Mongolian Envoy Lauds PM Modi’s Leadership, Hails India’s Growing Stature In World www.ommcomnews.com

New Delhi: Mongolia’s Ambassador to India, Ganbold Dambajav on Thursday lauded Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s leadership, highlighting that over 37 initiatives – including highly successful ‘Make In India’ and ‘Digital India’ – have been implemented since 2014.

In an exclusive interview with IANS, Dambajav called PM Modi “one of the most popular politicians in the world” citing his numerous achievements, including taking India towards becoming the third largest economy in the world in the near future.

“He is one of the most popular politicians in the world due to his achievements since he became the Prime Minister in 2014… We know that there are more than 37 initiatives that have come up during his tenure as Prime Minister. All have been improving the quality of life for the Indian people, bringing the businesses back to India. Make In India, Digital India, you name it, the last on the GST initiative. So, all those initiatives are bringing the well-being and prosperity for Indian people, Indian businesses, and opening India up to the world. Based on all those achievements, world is recognising Modi ji as the most popular and most renowned politician. So, I hope with his vision, in the near future, India will become the third economy in the world and there are more achievements that India can fulfill, reach during his tenure as Prime Minister,” Dambajav stated.

Several world leaders, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, US President Donald Trump, Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu, UAE President Mohamed Bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, Dominican PM Roosevelt Skerrit, Bhutanese PM Tshering Tobgay, Australian PM Anthony Albanese, New Zealand PM Christopher Luxon, Guyana President Irfaan Ali, former UK PM Rishi Sunak extended wishes to PM Modi on the occasion of his 75th birthday on Wednesday.

Extending greetings to PM Modi, the Mongolian Ambassador mentioned: “I would like to deliver a heartfelt congratulations and well-being wishes from the Mongolian people to Honourable Prime Minister Modi ji. I was happy enough today that we celebrated his birthday by planting tree, one of the initiatives of him, plant a tree in the name of your mother. So, I was very privileged to plant a tree in the mother’s name today morning along with my colleagues, ambassadors and high commissioners and other diplomats. I’m very happy to do it in the honour of the Prime Minister Modi ji. Mongolia and India, given our historic connectivity and lifestyle, are very peaceful countries. Together, we can do a lot to bring the stability and prosperity as well as peace, not only in our region but also all around the world.”

The diplomat recalled PM Modi’s State Visit to Mongolia in 2015, during which the Mongolian parliament had a special session on Sunday where the visiting leader delivered his remarks to the country’s lawmakers. The honour, he said, has been given to very few politicians or leaders around the world.

He noted that India and Mongolia are commemorating 70th anniversary of establishment of diplomatic ties in 2025.

Highlighting the cooperation between two nations in various sectors, he said, “Our bilateral relations go back to many centuries… We have a long rich heritage history in bilateral relations. With the historic visit of the Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Mongolia in 2015, our relations were elevated to the level of strategic partnership, which gave us a broad opportunity to enrich and deepen our partnerships, not only in political but also in the fields of defence, economy, health, education and the IT sector. For most of the Mongolians, India is a land of Lord Buddha. So, we have many Mongolians coming to India for worship or pilgrimage. Also, we have Mongolian monks studying long-term Buddhism in India.

“We also have many students who come in to study in India on the scholarship received from the ICCR besides for the short-term training through the high-tech programmes. So, there are a lot of opportunities and we see that economic cooperation is one of the engines of our bilateral relations. I’m happy to say that our pioneer project, the oil refinery, is now under construction and will be fully operational by 2027. It will provide the domestic use of 70 per cent of our petroleum and in the future if we enrich it, it can reach at a level of 100 per cent for our domestic usage,” he added.

(IANS)

...

Sonsy partners with Tuned Global to launch Mongolia’s first world-class music app www.gogo.mn

Sonsy launches Mongolia’s first world-class music streaming platform, powered by Tuned Global. Created to spotlight Mongolian artists and fans, Sonsy blends deep cultural roots with cutting-edge streaming technology, offering CD-quality sound, offline listening, and flexible subscription tiers.

More than just music, it opens fresh discovery and revenue channels for local creators, while ensuring listeners enjoy a premium, reliable service. Discover how Tuned Global and Mongol Content are shaping the future of Mongolia’s digital music scene and setting new standards for locally driven streaming innovation.

Mongolia is a small but mighty market, punching above its weight when it comes to music and fandom. Sonsy, the latest evolution in digital music in the country, is moving Mongolian digital culture forward. The goal: create a music service to rival global giants that’s custom-built to support Mongolian artists and music lovers. To do this, they turned to Tuned Global for best-in-class, turn-key music services.

A PLATFORM BUILT FOR MONGOLIAN ARTISTS AND FANS

Unlike international platforms and services, Sonsy is designed to strengthen the Mongolian music scene, supporting both emerging and established artists. Launched by Mongolmusic (the music distribution arm of Mongol Content LLC), Sonsy creates a new discovery channel for local fans and a new revenue channel for local artists. Along with royalties calculated per listen, Sonsy offers artists meaningful collaborations and promotional support to help them reach wider audiences in Mongolia and around the world. Sonsy also offers international-grade listening experiences, including CD-quality sound, gold-standard security and reliability, unlimited listening for subscribers, a freemium model with several subscription tiers (Individual, Duo and Family), and offline mode.

THE RISE OF SONSY AND MONGOLIA'S MUSIC CULTURE

To build Sonsy, Mongol Content LLC - Mongolia’s first content aggregator and a leading force in the country’s digital media and entertainment industry— used Tuned Global’s white-label streaming apps, a first for the Mongolian market. The partnership provided a highly efficient way to translate Mongol Content’s decades of regional expertise in media, music, and IP rights into a music service tailored to local tastes, needs, and listening habits

Unenbat Baatar, CEO of Mongolcontent, says, “Launching Sonsy marks a major milestone for Mongolia’s digital music industry. Backed by our 20 years of experience in the Mongolian market and long-standing support for local artists, Sonsy combines cultural heritage with cutting-edge technology. By partnering with Tuned Global, we gain from international expertise, and reliable streaming solutions enabling us to deliver a world-class experience while creating new opportunities for Mongolian talent to reach wider audiences”.

"We’re excited to partner with Sonsy to support the growth of Mongolia’s music industry,” explains Con Raso, Tuned Global’s Managing Director. “By combining our global streaming expertise with Sonsy’s local vision, we are delivering a world-class music experience that connects audiences with the artists they love. This partnership demonstrates how data and AI can enrich individuals' music journeys and unlock new opportunities for local creators."

Depression identified as leading cause of work inability www.ubpost.mn

World Mental Health Day will be observed on October 10. In anticipation of the day, the National Center for Mental Health (NCMH) and the “White Pen” Association of Health Care Journalists in Mongolia organized an informational session for journalists on mental health issues. In recent years, global attention has increasingly focused not only on physical health but also on mental and social well-being.

Worldwide, one in eight adults lives with a mental disorder. In 2005, mental and behavioral disorders accounted for 10 percent of all illnesses, rising to 15 percent by 2020. In Mongolia, according to the most recent survey conducted in 2013, one in four people suffers from a mental disorder.

Dr. N.Altanzul, Deputy Head of the Mental Health and Social Services Department at NCMH, highlighted that Mongolia lacks comprehensive research on the causes and circumstances of suicide. “Our suicide registration and reporting system is underdeveloped, and data from law enforcement and health agencies often conflict. Therefore, it is crucial to implement integrated measures starting with accurate reporting of suicides related to mental health issues,” she said.

Dr. N.Altanzul also noted that five of the 10 diseases most responsible for loss of work capacity are mental disorders, with depression remaining the leading cause of illness and disability across all age groups.

In addition, alcohol consumption has been identified as a factor in over 200 cases of orphanhood, mental illness, and injury. Globally, alcohol accounts for 5.3 percent of all deaths, with 13.5 percent of fatalities among 20 to 39-year-olds linked to alcohol and other intoxicants. Tobacco also remains a critical public health concern, with one person dying every four seconds worldwide due to smoking-related causes. Suicide ranks fourth among causes of death for 15 to 29-year-olds, with depression, anxiety, and behavioral disorders contributing significantly.

Mental health specialists emphasize that suicidal thoughts and impulses are intensely powerful feelings, and sharing them with someone can help “relieve” the burden. In Mongolia, individuals can also seek psychological support through the NCMH helpline at 1800–2000.

Monetary Policy Rate Maintained www.montsame.mn

The Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of Mongolia, at its meeting convened on September 15-16, resolved to maintain the policy rate at 12 percent. The decision was adopted in consideration of the prevailing economic, banking, and financial market conditions, as well as external and domestic developments and associated risks.

The resolution is aligned to stabilise inflation at the target level in the medium term and reinforce the resilience of the economy and the financial system. The Committee emphasised that subsequent monetary policy measures will be determined and implemented in accordance with changes in external and internal economic conditions, the trajectory of inflation, and the overall economic outlook.

As of August 2025, annual inflation stood at 8.8 percent nationwide and 9.8 percent in Ulaanbaatar. While inflation has gradually moderated since February due to the phased tightening of monetary and financial policy, August witnessed relative increases in the prices of meat, vegetables, and flour, thereby contributing to a renewed rise in food inflation.

Inflation is projected to ease gradually and fall within the target range in 2026. Nevertheless, Governor of the Bank of Mongolia B. Lkhagvasuren cautioned that government projects and their financing, export revenues, exchange rate fluctuations, supply constraints, and weather-related changes in food prices may continue to exert upward pressure on inflation.

In the first half of 2025, the economy expanded by 5.6 percent, with the agricultural sector serving as the principal driver of growth. In the latter half of the year, economic expansion is expected to be supported by increased production of copper concentrate and the commencement of new development projects.

Buuruljuut Power Plant’s Second Unit Set for December 2025 Commissioning www.montsame.mn

As Ulaanbaatar continues to account for over 60 percent of the country’s total energy consumption, efforts to support its energy infrastructure have made significant progress. In response to a projected 200 Megawatt (MW) capacity deficit for the winter of 2024-2025, the city successfully addressed the shortfall by commissioning the Buuruljuut power plant.

The 150 MW Buuruljuut facility, located in Bayanjargalan soum of Tuv aimag – approximately 120 kilometers southeast of Ulaanbaatar – was officially commissioned in October 2024 and connected to the central regional power grid in December 2024. The plant is part of a larger project to build a 600 MW power station in four units, based on the Buuruljuut brown coal deposit in the same region.

Unit I of the 150 MW plant has maintained an average daily load of 140 MW and delivered over 600 million kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity to the grid as of September 2025.

This development was made possible through a domestic market transaction, in which the capital city traded MNT 500 billion, allocating MNT 300 billion specifically for the Buuruljuut project. The investment marked a historic first for Ulaanbaatar in terms of domestic energy financing.

Officials have confirmed that the construction of Unit II, another 150 MW installation at the Buuruljuut site, is proceeding on schedule and is expected to be completed by December 5, 2025.

...

Capital Markets Mongolia Announces Mongolia Investment Forum: London 2025 at the London Stock Exchange www.newsfilecorp.com

Capital Markets Mongolia (CMM) today announced the Mongolia Investment Forum: London 2025, to be held on 22 October 2025 at the London Stock Exchange. The event marks a significant milestone in Mongolia's growing integration into global capital markets and follows the landmark listing of Invescore Financial Group on the London Stock Exchange earlier this year.

Mongolia Investment Forum: London 2025 will bring together leading Mongolian businesses, policymakers, international investors, and capital markets professionals to explore opportunities in equity investing, cross-border listings, impact investment, and fintech. The forum is hosted in partnership with the London Stock Exchange as the event's global partner and venue. Golomt Bank joins as the main sponsor, with ICFG Limited, a London Stock Exchange-listed firm, and StoneX Group, a Fortune 100 financial services company, also serving as sponsors.

The program will feature keynote addresses by senior government officials, including the Dorjkhand.T, Deputy Prime Minister of Mongolia and Fiona Blyth, the British Ambassador to Mongolia, alongside executives of Mongolia's leading companies. Global investors are invited to gain first-hand insight into Mongolia's market potential through in-depth panel discussions, company presentations, and private investor meetings.

"Mongolia's capital markets are experiencing a historic transformation, and this forum in London is a unique opportunity to connect Mongolia's financial institutions and enterprises with global investors," said Zolbayar Enkhbaatar, Founder & CEO of Capital Markets Mongolia. "We are proud to host this event at the London Stock Exchange and highlight the country's growing role in global capital flows."

About Capital Markets Mongolia

Capital Markets Mongolia is a leading advisory and research firm dedicated to advancing Mongolia's financial sector and capital markets ecosystem. Through high-level forums, investor outreach, and policy research, CMM works to connect international investors with Mongolian companies, institutions, and opportunities.

About Mongolia

Mongolia is one of the fastest-growing economies globally, with GDP growth projected at approximately 5.7% in 2025, supported by a recovery in agriculture and stable copper exports despite a decline in coal price. Fitch Ratings recently affirmed Mongolia's Long-Term Foreign-Currency Issuer Default Rating of 'B+' with a Stable Outlook, pointing to prudent fiscal management and resilient growth.

Visit www.capitalmarkets.mn/events/london-2025 for more information and registration.

- «

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

- 119

- 120

- 121

- 122

- 123

- 124

- 125

- 126

- 127

- 128

- 129

- 130

- 131

- 132

- 133

- 134

- 135

- 136

- 137

- 138

- 139

- 140

- 141

- 142

- 143

- 144

- 145

- 146

- 147

- 148

- 149

- 150

- 151

- 152

- 153

- 154

- 155

- 156

- 157

- 158

- 159

- 160

- 161

- 162

- 163

- 164

- 165

- 166

- 167

- 168

- 169

- 170

- 171

- 172

- 173

- 174

- 175

- 176

- 177

- 178

- 179

- 180

- 181

- 182

- 183

- 184

- 185

- 186

- 187

- 188

- 189

- 190

- 191

- 192

- 193

- 194

- 195

- 196

- 197

- 198

- 199

- 200

- 201

- 202

- 203

- 204

- 205

- 206

- 207

- 208

- 209

- 210

- 211

- 212

- 213

- 214

- 215

- 216

- 217

- 218

- 219

- 220

- 221

- 222

- 223

- 224

- 225

- 226

- 227

- 228

- 229

- 230

- 231

- 232

- 233

- 234

- 235

- 236

- 237

- 238

- 239

- 240

- 241

- 242

- 243

- 244

- 245

- 246

- 247

- 248

- 249

- 250

- 251

- 252

- 253

- 254

- 255

- 256

- 257

- 258

- 259

- 260

- 261

- 262

- 263

- 264

- 265

- 266

- 267

- 268

- 269

- 270

- 271

- 272

- 273

- 274

- 275

- 276

- 277

- 278

- 279

- 280

- 281

- 282

- 283

- 284

- 285

- 286

- 287

- 288

- 289

- 290

- 291

- 292

- 293

- 294

- 295

- 296

- 297

- 298

- 299

- 300

- 301

- 302

- 303

- 304

- 305

- 306

- 307

- 308

- 309

- 310

- 311

- 312

- 313

- 314

- 315

- 316

- 317

- 318

- 319

- 320

- 321

- 322

- 323

- 324

- 325

- 326

- 327

- 328

- 329

- 330

- 331

- 332

- 333

- 334

- 335

- 336

- 337

- 338

- 339

- 340

- 341

- 342

- 343

- 344

- 345

- 346

- 347

- 348

- 349

- 350

- 351

- 352

- 353

- 354

- 355

- 356

- 357

- 358

- 359

- 360

- 361

- 362

- 363

- 364

- 365

- 366

- 367

- 368

- 369

- 370

- 371

- 372

- 373

- 374

- 375

- 376

- 377

- 378

- 379

- 380

- 381

- 382

- 383

- 384

- 385

- 386

- 387

- 388

- 389

- 390

- 391

- 392

- 393

- 394

- 395

- 396

- 397

- 398

- 399

- 400

- 401

- 402

- 403

- 404

- 405

- 406

- 407

- 408

- 409

- 410

- 411

- 412

- 413

- 414

- 415

- 416

- 417

- 418

- 419

- 420

- 421

- 422

- 423

- 424

- 425

- 426

- 427

- 428

- 429

- 430

- 431

- 432

- 433

- 434

- 435

- 436

- 437

- 438

- 439

- 440

- 441

- 442

- 443

- 444

- 445

- 446

- 447

- 448

- 449

- 450

- 451

- 452

- 453

- 454

- 455

- 456

- 457

- 458

- 459

- 460

- 461

- 462

- 463

- 464

- 465

- 466

- 467

- 468

- 469

- 470

- 471

- 472

- 473

- 474

- 475

- 476

- 477

- 478

- 479

- 480

- 481

- 482

- 483

- 484

- 485

- 486

- 487

- 488

- 489

- 490

- 491

- 492

- 493

- 494

- 495

- 496

- 497

- 498

- 499

- 500

- 501

- 502

- 503

- 504

- 505

- 506

- 507

- 508

- 509

- 510

- 511

- 512

- 513

- 514

- 515

- 516

- 517

- 518

- 519

- 520

- 521

- 522

- 523

- 524

- 525

- 526

- 527

- 528

- 529

- 530

- 531

- 532

- 533

- 534

- 535

- 536

- 537

- 538

- 539

- 540

- 541

- 542

- 543

- 544

- 545

- 546

- 547

- 548

- 549

- 550

- 551

- 552

- 553

- 554

- 555

- 556

- 557

- 558

- 559

- 560

- 561

- 562

- 563

- 564

- 565

- 566

- 567

- 568

- 569

- 570

- 571

- 572

- 573

- 574

- 575

- 576

- 577

- 578

- 579

- 580

- 581

- 582

- 583

- 584

- 585

- 586

- 587

- 588

- 589

- 590

- 591

- 592

- 593

- 594

- 595

- 596

- 597

- 598

- 599

- 600

- 601

- 602

- 603

- 604

- 605

- 606

- 607

- 608

- 609

- 610

- 611

- 612

- 613

- 614

- 615

- 616

- 617

- 618

- 619

- 620

- 621

- 622

- 623

- 624

- 625

- 626

- 627

- 628

- 629

- 630

- 631

- 632

- 633

- 634

- 635

- 636

- 637

- 638

- 639

- 640

- 641

- 642

- 643

- 644

- 645

- 646

- 647

- 648

- 649

- 650

- 651

- 652

- 653

- 654

- 655

- 656

- 657

- 658

- 659

- 660

- 661

- 662

- 663

- 664

- 665

- 666

- 667

- 668

- 669

- 670

- 671

- 672

- 673

- 674

- 675

- 676

- 677

- 678

- 679

- 680

- 681

- 682

- 683

- 684

- 685

- 686

- 687

- 688

- 689

- 690

- 691

- 692

- 693

- 694

- 695

- 696

- 697

- 698

- 699

- 700

- 701

- 702

- 703

- 704

- 705

- 706

- 707

- 708

- 709

- 710

- 711

- 712

- 713

- 714

- 715

- 716

- 717

- 718

- 719

- 720

- 721

- 722

- 723

- 724

- 725

- 726

- 727

- 728

- 729

- 730

- 731

- 732

- 733

- 734

- 735

- 736

- 737

- 738

- 739

- 740

- 741

- 742

- 743

- 744

- 745

- 746

- 747

- 748

- 749

- 750

- 751

- 752

- 753

- 754

- 755

- 756

- 757

- 758

- 759

- 760

- 761

- 762

- 763

- 764

- 765

- 766

- 767

- 768

- 769

- 770

- 771

- 772

- 773

- 774

- 775

- 776

- 777

- 778

- 779

- 780

- 781

- 782

- 783

- 784

- 785

- 786

- 787

- 788

- 789

- 790

- 791

- 792

- 793

- 794

- 795

- 796

- 797

- 798

- 799

- 800

- 801

- 802

- 803

- 804

- 805

- 806

- 807

- 808

- 809

- 810

- 811

- 812

- 813

- 814

- 815

- 816

- 817

- 818

- 819

- 820

- 821

- 822

- 823

- 824

- 825

- 826

- 827

- 828

- 829

- 830

- 831

- 832

- 833

- 834

- 835

- 836

- 837

- 838

- 839

- 840

- 841

- 842

- 843

- 844

- 845

- 846

- 847

- 848

- 849

- 850

- 851

- 852

- 853

- 854

- 855

- 856

- 857

- 858

- 859

- 860

- 861

- 862

- 863

- 864

- 865

- 866

- 867

- 868

- 869

- 870

- 871

- 872

- 873

- 874

- 875

- 876

- 877

- 878

- 879

- 880

- 881

- 882

- 883

- 884

- 885

- 886

- 887

- 888

- 889

- 890

- 891

- 892

- 893

- 894

- 895

- 896

- 897

- 898

- 899

- 900

- 901

- 902

- 903

- 904

- 905

- 906

- 907

- 908

- 909

- 910

- 911

- 912

- 913

- 914

- 915

- 916

- 917

- 918

- 919

- 920

- 921

- 922

- 923

- 924

- 925

- 926

- 927

- 928

- 929

- 930

- 931

- 932

- 933

- 934

- 935

- 936

- 937

- 938

- 939

- 940

- 941

- 942

- 943

- 944

- 945

- 946

- 947

- 948

- 949

- 950

- 951

- 952

- 953

- 954

- 955

- 956

- 957

- 958

- 959

- 960

- 961

- 962

- 963

- 964

- 965

- 966

- 967

- 968

- 969

- 970

- 971

- 972

- 973

- 974

- 975

- 976

- 977

- 978

- 979

- 980

- 981

- 982

- 983

- 984

- 985

- 986

- 987

- 988

- 989

- 990

- 991

- 992

- 993

- 994

- 995

- 996

- 997

- 998

- 999

- 1000

- 1001

- 1002

- 1003

- 1004

- 1005

- 1006

- 1007

- 1008

- 1009

- 1010

- 1011

- 1012

- 1013

- 1014

- 1015

- 1016

- 1017

- 1018

- 1019

- 1020

- 1021

- 1022

- 1023

- 1024

- 1025

- 1026

- 1027

- 1028

- 1029

- 1030

- 1031

- 1032

- 1033

- 1034

- 1035

- 1036

- 1037

- 1038

- 1039

- 1040

- 1041

- 1042

- 1043

- 1044

- 1045

- 1046

- 1047

- 1048

- 1049

- 1050

- 1051

- 1052

- 1053

- 1054

- 1055

- 1056

- 1057

- 1058

- 1059

- 1060

- 1061

- 1062

- 1063

- 1064

- 1065

- 1066

- 1067

- 1068

- 1069

- 1070

- 1071

- 1072

- 1073

- 1074

- 1075

- 1076

- 1077

- 1078

- 1079

- 1080

- 1081

- 1082

- 1083

- 1084

- 1085

- 1086

- 1087

- 1088

- 1089

- 1090

- 1091

- 1092

- 1093

- 1094

- 1095

- 1096

- 1097

- 1098

- 1099

- 1100

- 1101

- 1102

- 1103

- 1104

- 1105

- 1106

- 1107

- 1108

- 1109

- 1110

- 1111

- 1112

- 1113

- 1114

- 1115

- 1116

- 1117

- 1118

- 1119

- 1120

- 1121

- 1122

- 1123

- 1124

- 1125

- 1126

- 1127

- 1128

- 1129

- 1130

- 1131

- 1132

- 1133

- 1134

- 1135

- 1136

- 1137

- 1138

- 1139

- 1140

- 1141

- 1142

- 1143

- 1144

- 1145

- 1146

- 1147

- 1148

- 1149

- 1150

- 1151

- 1152

- 1153

- 1154

- 1155

- 1156

- 1157

- 1158

- 1159

- 1160

- 1161

- 1162

- 1163

- 1164

- 1165

- 1166

- 1167

- 1168

- 1169

- 1170

- 1171

- 1172

- 1173

- 1174

- 1175

- 1176

- 1177

- 1178

- 1179

- 1180

- 1181

- 1182

- 1183

- 1184

- 1185

- 1186

- 1187

- 1188

- 1189

- 1190

- 1191

- 1192

- 1193

- 1194

- 1195

- 1196

- 1197

- 1198

- 1199

- 1200

- 1201

- 1202

- 1203

- 1204

- 1205

- 1206

- 1207

- 1208

- 1209

- 1210

- 1211

- 1212

- 1213

- 1214

- 1215

- 1216

- 1217

- 1218

- 1219

- 1220

- 1221

- 1222

- 1223

- 1224

- 1225

- 1226

- 1227

- 1228

- 1229

- 1230

- 1231

- 1232

- 1233

- 1234

- 1235

- 1236

- 1237

- 1238

- 1239

- 1240

- 1241

- 1242

- 1243

- 1244

- 1245

- 1246

- 1247

- 1248

- 1249

- 1250

- 1251

- 1252

- 1253

- 1254

- 1255

- 1256

- 1257

- 1258

- 1259

- 1260

- 1261

- 1262

- 1263

- 1264

- 1265

- 1266

- 1267

- 1268

- 1269

- 1270

- 1271

- 1272

- 1273

- 1274

- 1275

- 1276

- 1277

- 1278

- 1279

- 1280

- 1281

- 1282

- 1283

- 1284

- 1285

- 1286

- 1287

- 1288

- 1289

- 1290

- 1291

- 1292

- 1293

- 1294

- 1295

- 1296

- 1297

- 1298

- 1299

- 1300

- 1301

- 1302

- 1303

- 1304

- 1305

- 1306

- 1307

- 1308

- 1309

- 1310

- 1311

- 1312

- 1313

- 1314

- 1315

- 1316

- 1317

- 1318

- 1319

- 1320

- 1321

- 1322

- 1323

- 1324

- 1325

- 1326

- 1327

- 1328

- 1329

- 1330

- 1331

- 1332

- 1333

- 1334

- 1335

- 1336

- 1337

- 1338

- 1339

- 1340

- 1341

- 1342

- 1343

- 1344

- 1345

- 1346

- 1347

- 1348

- 1349

- 1350

- 1351

- 1352

- 1353

- 1354

- 1355

- 1356

- 1357

- 1358

- 1359

- 1360

- 1361

- 1362

- 1363

- 1364

- 1365

- 1366

- 1367

- 1368

- 1369

- 1370

- 1371

- 1372

- 1373

- 1374

- 1375

- 1376

- 1377

- 1378

- 1379

- 1380

- 1381

- 1382

- 1383

- 1384

- 1385

- 1386

- 1387

- 1388

- 1389

- 1390

- 1391

- 1392

- 1393

- 1394

- 1395

- 1396

- 1397

- 1398

- 1399

- 1400

- 1401

- 1402

- 1403

- 1404

- 1405

- 1406

- 1407

- 1408

- 1409

- 1410

- 1411

- 1412

- 1413

- 1414

- 1415

- 1416

- 1417

- 1418

- 1419

- 1420

- 1421

- 1422

- 1423

- 1424

- 1425

- 1426

- 1427

- 1428

- 1429

- 1430

- 1431

- 1432

- 1433

- 1434

- 1435

- 1436

- 1437

- 1438

- 1439

- 1440

- 1441

- 1442

- 1443

- 1444

- 1445

- 1446

- 1447

- 1448

- 1449

- 1450

- 1451

- 1452

- 1453

- 1454

- 1455

- 1456

- 1457

- 1458

- 1459

- 1460

- 1461

- 1462

- 1463

- 1464

- 1465

- 1466

- 1467

- 1468

- 1469

- 1470

- 1471

- 1472

- 1473

- 1474

- 1475

- 1476

- 1477

- 1478

- 1479

- 1480

- 1481

- 1482

- 1483

- 1484

- 1485

- 1486

- 1487

- 1488

- 1489

- 1490

- 1491

- 1492

- 1493

- 1494

- 1495

- 1496

- 1497

- 1498

- 1499

- 1500

- 1501

- 1502

- 1503

- 1504

- 1505

- 1506

- 1507

- 1508

- 1509

- 1510

- 1511

- 1512

- 1513

- 1514

- 1515

- 1516

- 1517

- 1518

- 1519

- 1520

- 1521

- 1522

- 1523

- 1524

- 1525

- 1526

- 1527

- 1528

- 1529

- 1530

- 1531

- 1532

- 1533

- 1534

- 1535

- 1536

- 1537

- 1538

- 1539

- 1540

- 1541

- 1542

- 1543

- 1544

- 1545

- 1546

- 1547

- 1548

- 1549

- 1550

- 1551

- 1552

- 1553

- 1554

- 1555

- 1556

- 1557

- 1558

- 1559

- 1560

- 1561

- 1562

- 1563

- 1564

- 1565

- 1566

- 1567

- 1568

- 1569

- 1570

- 1571

- 1572

- 1573

- 1574

- 1575

- 1576

- 1577

- 1578

- 1579

- 1580

- 1581

- 1582

- 1583

- 1584

- 1585

- 1586

- 1587

- 1588

- 1589

- 1590

- 1591

- 1592

- 1593

- 1594

- 1595

- 1596

- 1597

- 1598

- 1599

- 1600

- 1601

- 1602

- 1603

- 1604

- 1605

- 1606

- 1607

- 1608

- 1609

- 1610

- 1611

- 1612

- 1613

- 1614

- 1615

- 1616

- 1617

- 1618

- 1619

- 1620

- 1621

- 1622

- 1623

- 1624

- 1625

- 1626

- 1627

- 1628

- 1629

- 1630

- 1631

- 1632

- 1633

- 1634

- 1635

- 1636

- 1637

- 1638

- 1639

- 1640

- 1641

- 1642

- 1643

- 1644

- 1645

- 1646

- 1647

- 1648

- 1649

- 1650

- 1651

- 1652

- 1653

- 1654

- 1655

- 1656

- 1657

- 1658

- 1659

- 1660

- 1661

- 1662

- 1663

- 1664

- 1665

- 1666

- 1667

- 1668

- 1669

- 1670

- 1671

- 1672

- 1673

- 1674

- 1675

- 1676

- 1677

- 1678

- 1679

- 1680

- 1681

- 1682

- 1683

- 1684

- 1685

- 1686

- 1687

- 1688

- 1689

- 1690

- 1691

- 1692

- 1693

- 1694

- 1695

- 1696

- 1697

- 1698

- 1699

- 1700

- 1701

- 1702

- 1703

- 1704

- 1705

- 1706

- 1707

- 1708

- 1709

- 1710

- 1711

- 1712

- 1713

- 1714

- 1715

- 1716

- »