Events

| Name | organizer | Where |

|---|---|---|

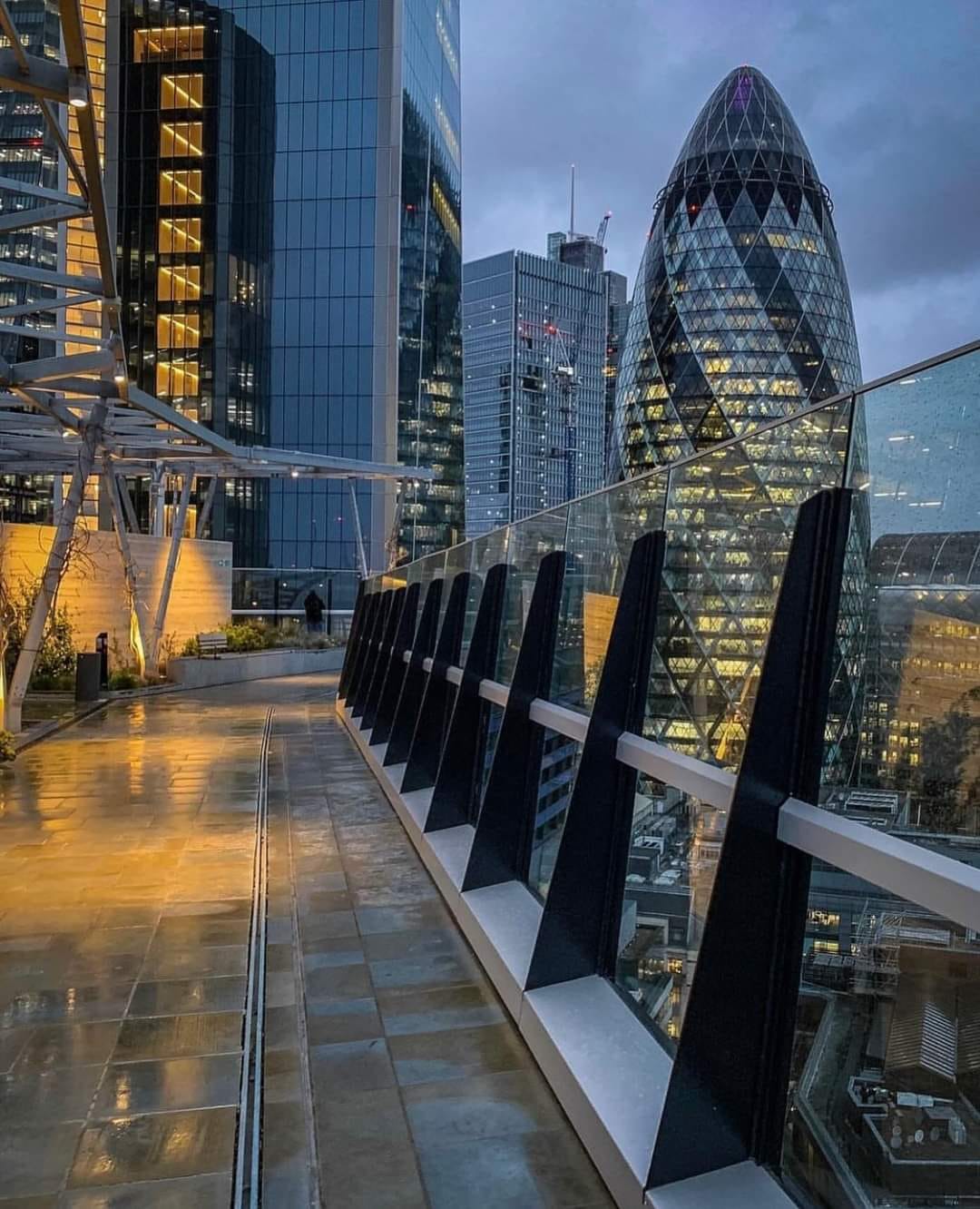

| MBCC “Doing Business with Mongolia seminar and Christmas Receptiom” Dec 10. 2025 London UK | MBCCI | London UK Goodman LLC |

NEWS

New Mongolian PM takes office after corruption protests www.afp.mn

Mongolian lawmakers on June 13 confirmed former top diplomat Gombojav Zandanshatar as the country’s new prime minister, after his predecessor resigned following weeks of anti-corruption protests.

Thousands of young people have demonstrated in the capital Ulaanbaatar in recent weeks, venting frustration at wealthy elites and what they see as pervasive corruption and injustice.

They called for then Prime Minister Luvsannamsrain Oyun-Erdene to step down and got their wish when the embattled leader announced his resignation last week.

Mr Zandanshatar – also from Mr Oyun-Erdene’s ruling Mongolian People’s Party (MPP) – was elected as his replacement in the early hours of Friday morning, with 108 out of 117 present voting in favour.

In a speech to lawmakers following his election, he stressed “the urgent need to stabilise the economy, improve the income and livelihood of its citizens”, according to a readout from the parliament.

The 52-year-old has been a fixture on Mongolia’s fractious political scene for around two decades and is seen as close to President Ukhnaa Khurelsukh.

He previously served as foreign minister and chief of staff to the president, as well as parliamentary speaker when the fledgling northern Asian democracy passed key constitutional reforms in 2019.

Before its recent political crisis, Mongolia had been ruled by a three-way coalition government since the 2024 elections resulted in a significantly reduced majority for Mr Oyun-Erdene’s MPP.

But in May, the MPP evicted its second-largest member, the Democratic Party (DP), from the coalition after some younger DP lawmakers backed calls for Mr Oyun-Erdene’s resignation.

That pushed Mr Oyun-Erdene to call a confidence vote in his own government, which he lost after DP lawmakers walked out of the chamber during the ballot.

Corruption ills

Mr Zandanshatar takes charge as Mongolia faces a combustive political cocktail of widespread corruption, rising living costs and concerns over the economy.

On the streets of Ulaanbaatar, prior to the vote, 38-year-old sociologist Tumentsetseg Purevdorj said his “political experience is a good asset”.

“But what we need is to have a strong and functional government,” she said.

“As a woman, I want him to include skilled woman representatives in the new cabinet.”

But other young Mongolians were sceptical that anything would change under the new prime minister.

“He has had high official status for over two decades,” Mr Bayaraa Surenjav, 37, told AFP.

“But I still can’t name a single good work he has done in those years.”

Mr Zoljargal Ganzereg, a 25-year-old economist, bemoaned the fact that “he was a politician when I was born and he is still up there”.

“Look at how we live, living paycheck to paycheck, barely affording the basic needs,” he said.

“If he can’t do anything about it, I have no choice but to move abroad.” AFP

Gold, Mined by Artisanal and Small-Scale Miners of Mongolia to Be Supplied to International Jewelry Companies www.montsame.mn

The Bank of Mongolia has signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Swiss Better Gold Association and Argor Heraeus, the precious metals refinery of Switzerland.

Under the Memorandum of Understanding, the parties will cooperate in supplying gold mined by artisanal and small-scale miners in Mongolia to international jewelry companies as raw materials. This will demonstrate that the gold mining and supply chain in Mongolia is transparent and reliable. Gold miners will also be given incentives for each kilogram of gold they deliver.

In the first phase, artisanal and small-scale miners operating in Bulgan aimag will be involved. The Bulgan aimag branch of the Bank of Mongolia and the Precious Metal Assay Laboratory of the Mongolian Agency for Standardization and Metrology will collaborate on the Project.

During the World Gold Council meeting held last year, along with the Central Banks of Colombia, Ecuador, and the Philippines, the Bank of Mongolia joined the “London Principles,” a set of principles aimed at formalizing the purchase of gold from artisanal and small-scale miners, supporting responsible artisanal mining, and integrating them into the formal supply chain.

Austria Publishes Synthesized Texts of Tax Treaties with Iceland, Kazakhstan and Mongolia as impacted by BEPS MLI www.orbitax.com

Austria's Ministry of Finance has published the synthesized texts of the tax treaties with Iceland, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia as impacted by the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (MLI). The synthesized texts have been prepared based on the reservations and notifications (MLI positions) submitted by the respective countries. The authentic legal texts of the tax treaties and the MLI take precedence and remain the legal texts applicable.

The MLI applies for the 2016 Austria-Iceland tax treaty:

with respect to taxes withheld at source on amounts paid or credited to non-residents, where the event giving rise to such taxes occurs on or after 1 January 2024; and

with respect to all other taxes, for taxes levied with respect to taxable periods beginning on or after 1 January 2025.

The MLI applies for the 2004 Austria-Kazakhstan tax treaty:

In Austria:

with respect to taxes withheld at source on amounts paid or credited to non-residents, where the event giving rise to such taxes occurs on or after 1 January 2024; and

with respect to all other taxes, for taxes levied with respect to taxable periods beginning on or after 1 January 2025;

In Kazakhstan:

with respect to taxes withheld at source on amounts paid or credited to non-residents, where the event giving rise to such taxes occurs on or after 1 January 2024; and

with respect to all other taxes, for taxes levied with respect to taxable periods beginning on or after 30 May 2024.

The MLI applies for the 2003 Austria-Mongolia tax treaty:

In Austria:

with respect to taxes withheld at source on amounts paid or credited to non-residents, where the event giving rise to such taxes occurs on or after 1 January 2025; and

with respect to all other taxes, for taxes levied with respect to taxable periods beginning on or after 1 January 2026;

In Mongolia:

with respect to taxes withheld at source on amounts paid or credited to non-residents, where the event giving rise to such taxes occurs on or after 1 January 2025; and

with respect to all other taxes, for taxes levied with respect to taxable periods beginning on or after 1 July 2025.

MLI synthesized texts of Austria's tax treaties can be found on the Ministry of Finance treaty webpage.

The United States and Mongolia Open the Center of Excellence for English Language Teaching in Ulaanbaatar www.mn.usembassy.gov

On June 12, representatives from the Government of Mongolia, the U.S. Embassy, and representatives of the diplomatic corps and international organizations, participated in the formal opening ceremony of the Center of Excellence for English Language Teaching, which is a joint partnership between the U.S. government, the Mongolian government, the National University of Mongolia, and other partners, including diplomatic missions and select companies.

The Center of Excellence for English Language Teaching is a key part of the U.S.-Mongolia Excellence in English Initiative. Since its soft opening in March, the Center has hosted an array of programs conducted by English Language Fellows, Fulbright English Teaching Assistants, Peace Corps volunteers, and other educators.

“Establishing the Center of Excellence marks a significant milestone in our shared commitment to advancing education and fostering professional development for English teachers across Mongolia,” U.S. Ambassador to Mongolia Richard Buangan said in remarks delivered at the National University of Mongolia on June 12. “This Center will serve as a hub for innovation, learning, and growth, providing invaluable resources and opportunities for Mongolian educators to enhance their skills and knowledge.”

The U.S. embassy supports a range of English language programs across Mongolia. These include the English Access Microscholarship Program, an after-school program for high school students that currently has 200 participants, and three U.S. English Language Fellows and seven Fulbright English Teaching Assistants, who work at local schools and colleges across the country.

...

Mongolia's 'Dragon Prince' dinosaur was forerunner of T. rex www.reuters.com

A newly identified mid-sized dinosaur from Mongolia dubbed the "Dragon Prince" has been identified as a pivotal forerunner of Tyrannosaurus rex in an illuminating discovery that has helped clarify the famous predator's complicated family history.

Named Khankhuuluu mongoliensis (pronounced khan-KOO-loo mon-gol-ee-EN-sis), it lived roughly 86 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period and was an immediate precursor to the dinosaur lineage called tyrannosaurs, which included some of the largest meat-eating land animals in Earth's history, among them T. rex. Khankhuuluu predated Tyrannosaurus by about 20 million years.

It was about 13 feet (4 meters) long, weighed about 1,600 pounds (750 kg), walked on two legs and had a lengthy snout with a mouthful of sharp teeth. More lightly built than T. rex, its body proportions indicate Khankhuuluu was fleet-footed, likely chasing down smaller prey such as bird-like dinosaurs called oviraptorosaurs and ornithomimosaurs. The largest-known T. rex specimen is 40-1/2 feet long (12.3 meters).

Khankhuuluu means "Dragon Prince" in the Mongolian language. Tyrannosaurus rex means "tyrant king of the lizards."

"In the name, we wanted to capture that Khankhuuluu was a small, early form that had not evolved into a king. It was still a prince," said paleontologist Darla Zelenitsky of the University of Calgary in Canada, co-author of the study published on Wednesday in the journal Nature, opens new tab.

Tyrannosaurs and all other meat-eating dinosaurs are part of a group called theropods. Tyrannosaurs appeared late in the age of dinosaurs, roaming Asia and North America.

Khankhuuluu shared many anatomical traits with tyrannosaurs but lacked certain defining characteristics, showing it was a predecessor and not a true member of the lineage.

"Khankhuuluu was almost a tyrannosaur, but not quite. For example, the bone along the top of the snout and the bones around the eye are somewhat different from what we see in tyrannosaurs. The snout bone was hollow and the bones around the eye didn't have all the horns and bumps seen in tyrannosaurs," Zelenitsky said.

"Khankhuuluu had teeth like steak knives, with serrations along both the front and back edges. Large tyrannosaurs had conical teeth and massive jaws that allowed them to bite with extreme force then hold in order to subdue very large prey. Khankhuuluu's more slender teeth and jaws show this animal took slashing bites to take down smaller prey," Zelenitsky added.

So the term rare earth elements, it refers to 17 chemically similar elements within the lanthanide series.

The researchers figured out its anatomy based on fossils of two Khankhuuluu individuals dug up in the 1970s but only now fully studied. These included parts of its skull, arms, legs, tail and back bones.

The Khankhuuluu remains, more complete than fossils of other known tyrannosaur forerunners, helped the researchers untangle this lineage's evolutionary history. They concluded that Khankhuuluu was the link between smaller forerunners of tyrannosaurs and later true tyrannosaurs, a transitional animal that reveals how these meat-eaters evolved from speedy and modestly sized species into giant apex predators.

"What started as the discovery of a new species ended up with us rewriting the family history of tyrannosaurs," said University of Calgary doctoral student and study lead author Jared Voris. "Before this, there was a lot of confusion about who was related to who when it came to tyrannosaur species."

Some scientists had hypothesized that smaller tyrannosaurs like China's Qianzhousaurus - dubbed "Pinnochio-rexes" because of their characteristic long snouts - reflected the lineage's ancestral form. That notion was contradicted by the fact that tyrannosaur forerunner Khankhuuluu differed from them in important ways.

"The tyrannosaur family didn't follow a straightforward path where they evolved from small size in early species to larger and larger sizes in later species," Zelenitsky said.

Voris noted that Khankhuuluu demonstrates that the ancestors to the tyrannosaurs lived in Asia.

"Around 85 million years ago, these tyrannosaur ancestors crossed a land bridge connecting Siberia and Alaska and evolved in North America into the apex predatory tyrannosaurs," Voris said.

One line of North American tyrannosaurs later trekked back to Asia and split into two branches - the "Pinnochio-rexes" and massive forms like Tarbosaurus, the researchers said. These apex predators then spread back to North America, they said, paving the way for the appearance of T. rex. Tyrannosaurus ruled western North America at the end of the age of dinosaurs when an asteroid struck Earth 66 million years ago.

"Khankhuuluu was where it all started but it was still only a distant ancestor of T. rex, at nearly 20 million years older," Zelenitsky said. "Over a dozen tyrannosaur species evolved in the time between them. It was a great-great-great uncle, sort of."

Reporting by Will Dunham in Washington, Editing by Rosalba O'Brien

Mongolia’s Pivot to Central Asia and the Caucasus: Strategic Realignments and Regional Implications www.cacianalyst.org

Mongolia's diplomatic engagement with Central Asia and the Caucasus marks a pivotal evolution of its "third neighbor" strategy, aimed at strengthening partnerships beyond its traditional ties with Russia and China. This strategic shift has gained urgency in light of changing regional dynamics within Greater Central Asia. Since 2020, Mongolia has intensified its diplomatic activities, exemplified by presidential visits to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan in 2024. Economic interactions, while still modest, show promising growth, notably in trade with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, where exports have notably increased. These developments align with broader regional trends towards greater independence from Russia and China, as Central Asian countries seek to establish cooperative mechanisms. Ultimately, Mongolia's westward pivot not only enhances its sovereignty but positions it as a crucial player in promoting regional stability and cooperation in the evolving Eurasian geopolitical landscape.

BACKGROUND: Mongolia's diplomatic engagement with Central Asia and the Caucasus represents the latest evolution of its third neighbor strategy—a long-standing policy aimed at cultivating partnerships beyond Russia and China to enhance Mongolia’s sovereignty. This westward pivot has emerged as a strategic necessity for Mongolia, particularly as regional dynamics across Greater Central Asia undergo significant transformation.

Mongolia's diplomatic activity with Central Asia has accelerated markedly since 2020. High-level visits, previously sporadic, have become increasingly frequent and substantive. President Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh's recent state visits to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan in 2024 resulted in numerous bilateral agreements, bolstering cooperation in trade, transport, and cultural exchange. The visit to Uzbekistan yielded 14 bilateral agreements and the inauguration of Mongolia's Embassy in Tashkent. Similarly, the Kazakhstan visit established a formal strategic partnership. Mongolia's diplomatic outreach extended to Turkmenistan, marking the first bilateral presidential visits since diplomatic relations began in 1992, and to Kyrgyzstan, where bilateral relations have steadily improved following President Sadyr Japarov's 2023 visit to Mongolia and the opening of the Kyrgyz Embassy in Ulaanbaatar.

Economic engagement, while still modest, demonstrates upward momentum. Trade with Kazakhstan has reached approximately $150 million annually, with Mongolian exports of horse meat growing from $2.9 million in 2017 to $8.3 million in 2022. Kazakhstan's exports to Mongolia, primarily industrial and consumer goods, increased from approximately $72.9 million to $93 million during the same period. Mongolia's trade with Kyrgyzstan doubled from about $2 million in 2017 to over $5 million by 2022, driven by re-exported used cars and consumer goods. Trade with Uzbekistan grew dramatically from under $1 million in 2017 to nearly $10 million by 2022, focused on meat exports and Uzbek fertilizers. Meanwhile, trade with Turkmenistan and Tajikistan remains negligible. For Mongolia, with $20 billion GDP and over 90% of export goes to China, this is a significant development.

Mongolia's engagement with the Caucasus remains nascent but shows promising signs. High-level diplomatic exchanges include former President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj's official visits to Armenia in 2015 and Georgia in 2016, enhancing trade and cultural ties. Azerbaijan received a working visit from former President Khaltmaagiin Battulga in 2018, exploring collaborations in energy and investment. While trade volumes remain limited, recent growth is evident, particularly with Azerbaijan, where exports surged to approximately $1.6 million in 2024, primarily in livestock products.

These developments have occurred against the backdrop of emerging region-wide structures in Greater Central Asia, as countries seek to develop collective mechanisms for cooperation outside the frameworks dominated by Russia and China. Mongolia's engagement with these structures aligns with the broader regional trend toward developing greater agency and connectivity across Central Asia and the Caucasus.

IMPLICATIONS: Mongolia's deepening engagement with Central Asia and the Caucasus presents crucial economic and strategic diversification opportunities. Enhanced diplomatic and economic ties provide Mongolia with a hedge against over-reliance on China, currently its dominant trading partner, and alternative options given restrictive Western sanctions against Russia. The geographic and economic profiles of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, with their combined population of approximately 56 million, offer ample market opportunities for Mongolia.

Politically, Mongolia's democratic governance, a distinctive feature in the region, offers a stable and transparent framework for engagement. This reliability in governance and commitment to international norms facilitates more predictable and trustworthy partnerships in areas crucial for regional development, such as trade facilitation, infrastructure investment, and the establishment of robust legal frameworks for transport corridors. This unique identity enhances Mongolia's value to Western partners and provides a practical model for how democratic principles can support economic and strategic cooperation in a challenging geopolitical landscape. Furthermore, Mongolia's active participation in cultural events like the World Nomad Games reinforces shared heritage with Central Asian states, promoting a regional identity that bridges East and West.

The integration into regional mechanisms offers Mongolia access to emerging transport corridors, particularly the "Middle Corridor" that connects Asia to Europe without crossing Russian territory. This connectivity could mitigate Mongolia's landlocked status and provide more direct routes to global markets. The successful development of these corridors would significantly reduce Mongolia's vulnerability to geopolitical pressures from its immediate neighbors.

Central Asian and Caucasus countries benefit from Mongolia's outreach through expanded diplomatic networks and opportunities for collaborative initiatives in transport, energy, agriculture, environment and mining. Mongolia's strategic neutrality and pragmatic foreign policy approach are viewed positively in the region, enabling enhanced collaboration without triggering sensitive geopolitical responses from Russia and China.

The burgeoning regional integration subtly shifts dynamics for Russia and China. Although both powers are likely to tolerate Mongolia's increased engagement due to its non-military, primarily economic and diplomatic nature, deeper regional cooperation could eventually dilute their influence. Increased regional activity that transcends Russian and Chinese dominance, along with coordinated economic policies, could reduce regional dependency on Moscow and Beijing, leading to cautious observation from both capitals.

China's Belt and Road Initiative has significantly shaped regional infrastructure development, but Mongolia's growing ties with Central Asia introduce an alternative approach to connectivity that might circumvent Beijing's leverage. Similarly, Russia's attempts to maintain regional influence through the Eurasian Economic Union face challenges as Mongolia and Central Asian states pursue more diverse partnerships. This diversification of regional relationships represents a gradual but significant shift in the geopolitical landscape.

Mongolia's third neighbors (the U.S., EU, India, Japan, South Korea, and Turkiye) view this westward pivot positively. Strengthening Mongolia's regional ties aligns with broader Western strategic goals, including promoting stability and sovereignty in Central Asia. High-profile European visits to Mongolia, followed by tours to Central Asia (e.g., French President Emmanuel Macron’s and former UK Foreign Secretary David Cameron’s multi-leg visits), illustrate growing interest in Mongolia's bridging role. These engagements allow Western countries to enhance their regional presence without being perceived as exclusively engaging with authoritarian regimes.

The U.S., which has traditionally engaged Central Asia through the C5+1 format, could consider integrating Mongolia into this dialogue, potentially transforming it into a C6+1 arrangement. As outlined in the American Foreign Policy Council's (AFPC) April 2025 report, such integration would better reflect Mongolia's shared strategic and economic challenges with the region, particularly in critical minerals essential to global supply chains. Similarly, Japan and South Korea recognize Mongolia's potential as a gateway to continental Asia, leveraging soft power and economic investments to enhance regional integration.

CONCLUSIONS: Mongolia's pivot toward Central Asia and the Caucasus is driven by strategic necessity and presents significant opportunities for regional integration. The past years' diplomatic and economic initiatives signal genuine, albeit incremental, progress. Although concrete outcomes remain limited, the diplomatic momentum could lead to substantive cooperation in trade, transport, and infrastructure.

For Mongolia, regional integration serves as a diplomatic insurance policy, enhancing strategic autonomy amid geopolitical uncertainty. The pragmatic approach toward bilateral and multilateral cooperation mitigates potential pressure from Russia and China while strengthening ties with Western democracies. The development of region-wide structures that exclude external powers could create space for greater collective agency among the states of Greater Central Asia, including Mongolia.

Mongolia's westward orientation strategically positions it as a significant actor capable of bridging regional divides, promoting economic cooperation, and advocating democratic governance. As suggested in the AFPC’s strategy document, the emergence of a more integrated Greater Central Asia, including Mongolia, could serve as a stabilizing force across the region. Whether this evolves into more tangible regional integration or remains predominantly at the diplomatic level will significantly impact Mongolia's role in the evolving Eurasian geopolitical landscape.

The increasing American strategic interest in Greater Central Asia, with its emphasis on developing exclusive region-wide structures and enhancing connectivity, aligns with Mongolia's objectives. This convergence of interests offers Mongolia an opportunity to reinforce its sovereignty through regional integration while contributing to a more balanced regional order less dominated by Russia and China. In this evolving framework, Mongolia's distinctive political identity and strategic positioning could turn the country into an indispensable player.

AUTHORS’ BIOS: Chimguundari Navaan-Yunden is an Ambassador-at-Large and a former Foreign Policy Advisor to the Prime Minister of Mongolia. Tuvshinzaya Gantulga is a Nonresident Fellow at the Mongolian National Institute for Security Studies and a former foreign policy aide to the President of Mongolia. Both are alumni of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute Rumsfeld Fellowship Program and members of the CAMCA Network.

Electronic waste from Kyrgyzstan to be recycled at plant in Mongolia www.24.kg

Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Kyrgyz Republic to Mongolia Aibek Artykbaev took part in the official opening ceremony of a plant for sorting and recycling electronic waste in Mongolia. The press service of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported.

According to it, the enterprise was created as part of joint cooperation between private companies of Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia and Japan with the support of JICA.

«In order to further implement the project, it is planned to establish systematic supplies of electronic waste from Kyrgyzstan for subsequent processing at the new plant. In 2024, representatives of Japanese and Mongolian companies visited Kyrgyzstan and conducted a preliminary assessment of the potential for the supply of electronic components for recycling,» the statement says.

At the initial stage of cooperation, the first batch of used computer circuit boards was purchased in Kyrgyzstan and exported to Mongolia.

«Implementation of the project represents an important contribution to the development of international cooperation in the field of environmentally friendly recycling of electronic waste and contributes to strengthening economic ties between Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia and Japan,» the Foreign Ministry reported.

Playtime Festival to Welcome 100,000 Attendees www.montsame.mn

The Playtime Festival 2025, which aspires to become one of Asia’s top five leading music festivals, will be held on July 3-6, 2025, at Playtime Field, Ulaanbaatar.

The 23rd Playtime Festival is preparing to host 100,000 attendees over four days, creating 3,000 temporary jobs and partnering with over 200 businesses. As a result, it is estimated to generate MNT 12 billion in added value to Ulaanbaatar's economy.

Regarding this year’s Festival, Natsagdorj Tserendorj, Founder of Playtime Festival, said, “This year is notable by the introduction of two important new technologies: QR-coded tickets and a cashless payment system using wristbands. These advancements offer numerous advantages, particularly in ensuring the safety of attendees. One of the common issues is the counterfeiting and illegal sale of tickets. The adoption of these technologies is a critical step in protecting our audience. Paying with wristbands will help prevent long queues and eliminate the risk of losing cash or bank cards. In addition, sanitation facilities have been upgraded, and camping areas are now free of charge, which is another benefit. Previously, young people had to travel back and forth to Ulaanbaatar, covering up to 100 kilometers. Instead, they can now come dressed warmly and stay comfortably on-site. This year, we are operating with the objective of delivering a genuine camping festival experience. We aim to offer each attendee a musical experience unlike anything they have encountered before.”

Last year, the Festival attracted 72,000 attendees and is aiming at becoming one of Asia’s top five music festivals by 2027. This year, performances will be delivered by 37 international and 67 domestic bands and artists across eight stages. Some notable international acts include:

Alcest (France) - Post-metal

Envy (Japan) - Post-hardcore

Jambinai (South Korea) - Post-rock

YHWH Nailgun (USA) - Alternative/Indie, Dance/Electronic, Rock

Balming Tiger (South Korea) - Hip-Hop/Rap

Megumi Acorda (Philippines) - Indie Pop

Selica Gel (South Korea) - Indie Rock

VVAS (Thailand) - Post-punk, Indie Rock

The Festival, held under the motto “Earth. Music. Art. Love,” is selling tickets through Shoppy.mn, with discounted prices available until July 3, 2025.

Chinese servicemen to take part in peacekeeping exercise in Mongolia www.akipress.com

China's People's Liberation Army (PLA) detachment will set off for Mongolia in mid-June to participate in the "Khaan Quest-2025" multinational peacekeeping exercise, Xinhua reports with reference to a defense spokesperson.

The PLA detachment is at the invitation of Mongolia's Ministry of Defense, said Jiang Bin, spokesperson for China's Ministry of National Defense, at a press conference.

Jiang also announced that the 20th meeting of the Experts' Working Group on Peacekeeping Operations under the ASEAN Defense Ministers' Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus) will be held in the city of Nanjing in Jiangsu Province, east China, from June 11 to 14.

The member states and observer states of the ADMM-Plus, as well as the United Nations and the ASEAN Secretariat will send representatives to the event, which aims to deepen military mutual trust and security cooperation among regional countries and enhance their capacities for peacekeeping operations, he said.

Jade Gas Holdings commissions Mongolia's first horizontal coal bed methane well www.akipress.com

Jade Gas Holdings Limited (ASX:JGH) said it had become the first company to commission a horizontal coal bed methane (CBM) well in Mongolia.

The company has achieved a significant milestone by commencing production from its first two Coal Bed Methane (CBM) gas wells in Mongolia's South Gobi region.

Jade Gas Holdings is actively pursuing partnerships to commercialize its gas production, aiming to replace diesel fuel with natural gas for transportation and power generation, which could lead to early revenue opportunities.

The company operates in the energy sector, focusing on the exploration and production of Coal Bed Methane (CBM) gas. It is primarily engaged in developing gas resources in Mongolia, with a market focus on providing cleaner energy solutions to replace diesel fuel in transportation and power generation sectors.

"Jade continues to discuss these near-term commercialization opportunities with partners, focusing on liquefied natural gas (LNG) and compressed natural gas (CNG) opportunities for revenue generation," Jade added, a sentiment supported by company chief executive Dennis Morton.

- «

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

- 119

- 120

- 121

- 122

- 123

- 124

- 125

- 126

- 127

- 128

- 129

- 130

- 131

- 132

- 133

- 134

- 135

- 136

- 137

- 138

- 139

- 140

- 141

- 142

- 143

- 144

- 145

- 146

- 147

- 148

- 149

- 150

- 151

- 152

- 153

- 154

- 155

- 156

- 157

- 158

- 159

- 160

- 161

- 162

- 163

- 164

- 165

- 166

- 167

- 168

- 169

- 170

- 171

- 172

- 173

- 174

- 175

- 176

- 177

- 178

- 179

- 180

- 181

- 182

- 183

- 184

- 185

- 186

- 187

- 188

- 189

- 190

- 191

- 192

- 193

- 194

- 195

- 196

- 197

- 198

- 199

- 200

- 201

- 202

- 203

- 204

- 205

- 206

- 207

- 208

- 209

- 210

- 211

- 212

- 213

- 214

- 215

- 216

- 217

- 218

- 219

- 220

- 221

- 222

- 223

- 224

- 225

- 226

- 227

- 228

- 229

- 230

- 231

- 232

- 233

- 234

- 235

- 236

- 237

- 238

- 239

- 240

- 241

- 242

- 243

- 244

- 245

- 246

- 247

- 248

- 249

- 250

- 251

- 252

- 253

- 254

- 255

- 256

- 257

- 258

- 259

- 260

- 261

- 262

- 263

- 264

- 265

- 266

- 267

- 268

- 269

- 270

- 271

- 272

- 273

- 274

- 275

- 276

- 277

- 278

- 279

- 280

- 281

- 282

- 283

- 284

- 285

- 286

- 287

- 288

- 289

- 290

- 291

- 292

- 293

- 294

- 295

- 296

- 297

- 298

- 299

- 300

- 301

- 302

- 303

- 304

- 305

- 306

- 307

- 308

- 309

- 310

- 311

- 312

- 313

- 314

- 315

- 316

- 317

- 318

- 319

- 320

- 321

- 322

- 323

- 324

- 325

- 326

- 327

- 328

- 329

- 330

- 331

- 332

- 333

- 334

- 335

- 336

- 337

- 338

- 339

- 340

- 341

- 342

- 343

- 344

- 345

- 346

- 347

- 348

- 349

- 350

- 351

- 352

- 353

- 354

- 355

- 356

- 357

- 358

- 359

- 360

- 361

- 362

- 363

- 364

- 365

- 366

- 367

- 368

- 369

- 370

- 371

- 372

- 373

- 374

- 375

- 376

- 377

- 378

- 379

- 380

- 381

- 382

- 383

- 384

- 385

- 386

- 387

- 388

- 389

- 390

- 391

- 392

- 393

- 394

- 395

- 396

- 397

- 398

- 399

- 400

- 401

- 402

- 403

- 404

- 405

- 406

- 407

- 408

- 409

- 410

- 411

- 412

- 413

- 414

- 415

- 416

- 417

- 418

- 419

- 420

- 421

- 422

- 423

- 424

- 425

- 426

- 427

- 428

- 429

- 430

- 431

- 432

- 433

- 434

- 435

- 436

- 437

- 438

- 439

- 440

- 441

- 442

- 443

- 444

- 445

- 446

- 447

- 448

- 449

- 450

- 451

- 452

- 453

- 454

- 455

- 456

- 457

- 458

- 459

- 460

- 461

- 462

- 463

- 464

- 465

- 466

- 467

- 468

- 469

- 470

- 471

- 472

- 473

- 474

- 475

- 476

- 477

- 478

- 479

- 480

- 481

- 482

- 483

- 484

- 485

- 486

- 487

- 488

- 489

- 490

- 491

- 492

- 493

- 494

- 495

- 496

- 497

- 498

- 499

- 500

- 501

- 502

- 503

- 504

- 505

- 506

- 507

- 508

- 509

- 510

- 511

- 512

- 513

- 514

- 515

- 516

- 517

- 518

- 519

- 520

- 521

- 522

- 523

- 524

- 525

- 526

- 527

- 528

- 529

- 530

- 531

- 532

- 533

- 534

- 535

- 536

- 537

- 538

- 539

- 540

- 541

- 542

- 543

- 544

- 545

- 546

- 547

- 548

- 549

- 550

- 551

- 552

- 553

- 554

- 555

- 556

- 557

- 558

- 559

- 560

- 561

- 562

- 563

- 564

- 565

- 566

- 567

- 568

- 569

- 570

- 571

- 572

- 573

- 574

- 575

- 576

- 577

- 578

- 579

- 580

- 581

- 582

- 583

- 584

- 585

- 586

- 587

- 588

- 589

- 590

- 591

- 592

- 593

- 594

- 595

- 596

- 597

- 598

- 599

- 600

- 601

- 602

- 603

- 604

- 605

- 606

- 607

- 608

- 609

- 610

- 611

- 612

- 613

- 614

- 615

- 616

- 617

- 618

- 619

- 620

- 621

- 622

- 623

- 624

- 625

- 626

- 627

- 628

- 629

- 630

- 631

- 632

- 633

- 634

- 635

- 636

- 637

- 638

- 639

- 640

- 641

- 642

- 643

- 644

- 645

- 646

- 647

- 648

- 649

- 650

- 651

- 652

- 653

- 654

- 655

- 656

- 657

- 658

- 659

- 660

- 661

- 662

- 663

- 664

- 665

- 666

- 667

- 668

- 669

- 670

- 671

- 672

- 673

- 674

- 675

- 676

- 677

- 678

- 679

- 680

- 681

- 682

- 683

- 684

- 685

- 686

- 687

- 688

- 689

- 690

- 691

- 692

- 693

- 694

- 695

- 696

- 697

- 698

- 699

- 700

- 701

- 702

- 703

- 704

- 705

- 706

- 707

- 708

- 709

- 710

- 711

- 712

- 713

- 714

- 715

- 716

- 717

- 718

- 719

- 720

- 721

- 722

- 723

- 724

- 725

- 726

- 727

- 728

- 729

- 730

- 731

- 732

- 733

- 734

- 735

- 736

- 737

- 738

- 739

- 740

- 741

- 742

- 743

- 744

- 745

- 746

- 747

- 748

- 749

- 750

- 751

- 752

- 753

- 754

- 755

- 756

- 757

- 758

- 759

- 760

- 761

- 762

- 763

- 764

- 765

- 766

- 767

- 768

- 769

- 770

- 771

- 772

- 773

- 774

- 775

- 776

- 777

- 778

- 779

- 780

- 781

- 782

- 783

- 784

- 785

- 786

- 787

- 788

- 789

- 790

- 791

- 792

- 793

- 794

- 795

- 796

- 797

- 798

- 799

- 800

- 801

- 802

- 803

- 804

- 805

- 806

- 807

- 808

- 809

- 810

- 811

- 812

- 813

- 814

- 815

- 816

- 817

- 818

- 819

- 820

- 821

- 822

- 823

- 824

- 825

- 826

- 827

- 828

- 829

- 830

- 831

- 832

- 833

- 834

- 835

- 836

- 837

- 838

- 839

- 840

- 841

- 842

- 843

- 844

- 845

- 846

- 847

- 848

- 849

- 850

- 851

- 852

- 853

- 854

- 855

- 856

- 857

- 858

- 859

- 860

- 861

- 862

- 863

- 864

- 865

- 866

- 867

- 868

- 869

- 870

- 871

- 872

- 873

- 874

- 875

- 876

- 877

- 878

- 879

- 880

- 881

- 882

- 883

- 884

- 885

- 886

- 887

- 888

- 889

- 890

- 891

- 892

- 893

- 894

- 895

- 896

- 897

- 898

- 899

- 900

- 901

- 902

- 903

- 904

- 905

- 906

- 907

- 908

- 909

- 910

- 911

- 912

- 913

- 914

- 915

- 916

- 917

- 918

- 919

- 920

- 921

- 922

- 923

- 924

- 925

- 926

- 927

- 928

- 929

- 930

- 931

- 932

- 933

- 934

- 935

- 936

- 937

- 938

- 939

- 940

- 941

- 942

- 943

- 944

- 945

- 946

- 947

- 948

- 949

- 950

- 951

- 952

- 953

- 954

- 955

- 956

- 957

- 958

- 959

- 960

- 961

- 962

- 963

- 964

- 965

- 966

- 967

- 968

- 969

- 970

- 971

- 972

- 973

- 974

- 975

- 976

- 977

- 978

- 979

- 980

- 981

- 982

- 983

- 984

- 985

- 986

- 987

- 988

- 989

- 990

- 991

- 992

- 993

- 994

- 995

- 996

- 997

- 998

- 999

- 1000

- 1001

- 1002

- 1003

- 1004

- 1005

- 1006

- 1007

- 1008

- 1009

- 1010

- 1011

- 1012

- 1013

- 1014

- 1015

- 1016

- 1017

- 1018

- 1019

- 1020

- 1021

- 1022

- 1023

- 1024

- 1025

- 1026

- 1027

- 1028

- 1029

- 1030

- 1031

- 1032

- 1033

- 1034

- 1035

- 1036

- 1037

- 1038

- 1039

- 1040

- 1041

- 1042

- 1043

- 1044

- 1045

- 1046

- 1047

- 1048

- 1049

- 1050

- 1051

- 1052

- 1053

- 1054

- 1055

- 1056

- 1057

- 1058

- 1059

- 1060

- 1061

- 1062

- 1063

- 1064

- 1065

- 1066

- 1067

- 1068

- 1069

- 1070

- 1071

- 1072

- 1073

- 1074

- 1075

- 1076

- 1077

- 1078

- 1079

- 1080

- 1081

- 1082

- 1083

- 1084

- 1085

- 1086

- 1087

- 1088

- 1089

- 1090

- 1091

- 1092

- 1093

- 1094

- 1095

- 1096

- 1097

- 1098

- 1099

- 1100

- 1101

- 1102

- 1103

- 1104

- 1105

- 1106

- 1107

- 1108

- 1109

- 1110

- 1111

- 1112

- 1113

- 1114

- 1115

- 1116

- 1117

- 1118

- 1119

- 1120

- 1121

- 1122

- 1123

- 1124

- 1125

- 1126

- 1127

- 1128

- 1129

- 1130

- 1131

- 1132

- 1133

- 1134

- 1135

- 1136

- 1137

- 1138

- 1139

- 1140

- 1141

- 1142

- 1143

- 1144

- 1145

- 1146

- 1147

- 1148

- 1149

- 1150

- 1151

- 1152

- 1153

- 1154

- 1155

- 1156

- 1157

- 1158

- 1159

- 1160

- 1161

- 1162

- 1163

- 1164

- 1165

- 1166

- 1167

- 1168

- 1169

- 1170

- 1171

- 1172

- 1173

- 1174

- 1175

- 1176

- 1177

- 1178

- 1179

- 1180

- 1181

- 1182

- 1183

- 1184

- 1185

- 1186

- 1187

- 1188

- 1189

- 1190

- 1191

- 1192

- 1193

- 1194

- 1195

- 1196

- 1197

- 1198

- 1199

- 1200

- 1201

- 1202

- 1203

- 1204

- 1205

- 1206

- 1207

- 1208

- 1209

- 1210

- 1211

- 1212

- 1213

- 1214

- 1215

- 1216

- 1217

- 1218

- 1219

- 1220

- 1221

- 1222

- 1223

- 1224

- 1225

- 1226

- 1227

- 1228

- 1229

- 1230

- 1231

- 1232

- 1233

- 1234

- 1235

- 1236

- 1237

- 1238

- 1239

- 1240

- 1241

- 1242

- 1243

- 1244

- 1245

- 1246

- 1247

- 1248

- 1249

- 1250

- 1251

- 1252

- 1253

- 1254

- 1255

- 1256

- 1257

- 1258

- 1259

- 1260

- 1261

- 1262

- 1263

- 1264

- 1265

- 1266

- 1267

- 1268

- 1269

- 1270

- 1271

- 1272

- 1273

- 1274

- 1275

- 1276

- 1277

- 1278

- 1279

- 1280

- 1281

- 1282

- 1283

- 1284

- 1285

- 1286

- 1287

- 1288

- 1289

- 1290

- 1291

- 1292

- 1293

- 1294

- 1295

- 1296

- 1297

- 1298

- 1299

- 1300

- 1301

- 1302

- 1303

- 1304

- 1305

- 1306

- 1307

- 1308

- 1309

- 1310

- 1311

- 1312

- 1313

- 1314

- 1315

- 1316

- 1317

- 1318

- 1319

- 1320

- 1321

- 1322

- 1323

- 1324

- 1325

- 1326

- 1327

- 1328

- 1329

- 1330

- 1331

- 1332

- 1333

- 1334

- 1335

- 1336

- 1337

- 1338

- 1339

- 1340

- 1341

- 1342

- 1343

- 1344

- 1345

- 1346

- 1347

- 1348

- 1349

- 1350

- 1351

- 1352

- 1353

- 1354

- 1355

- 1356

- 1357

- 1358

- 1359

- 1360

- 1361

- 1362

- 1363

- 1364

- 1365

- 1366

- 1367

- 1368

- 1369

- 1370

- 1371

- 1372

- 1373

- 1374

- 1375

- 1376

- 1377

- 1378

- 1379

- 1380

- 1381

- 1382

- 1383

- 1384

- 1385

- 1386

- 1387

- 1388

- 1389

- 1390

- 1391

- 1392

- 1393

- 1394

- 1395

- 1396

- 1397

- 1398

- 1399

- 1400

- 1401

- 1402

- 1403

- 1404

- 1405

- 1406

- 1407

- 1408

- 1409

- 1410

- 1411

- 1412

- 1413

- 1414

- 1415

- 1416

- 1417

- 1418

- 1419

- 1420

- 1421

- 1422

- 1423

- 1424

- 1425

- 1426

- 1427

- 1428

- 1429

- 1430

- 1431

- 1432

- 1433

- 1434

- 1435

- 1436

- 1437

- 1438

- 1439

- 1440

- 1441

- 1442

- 1443

- 1444

- 1445

- 1446

- 1447

- 1448

- 1449

- 1450

- 1451

- 1452

- 1453

- 1454

- 1455

- 1456

- 1457

- 1458

- 1459

- 1460

- 1461

- 1462

- 1463

- 1464

- 1465

- 1466

- 1467

- 1468

- 1469

- 1470

- 1471

- 1472

- 1473

- 1474

- 1475

- 1476

- 1477

- 1478

- 1479

- 1480

- 1481

- 1482

- 1483

- 1484

- 1485

- 1486

- 1487

- 1488

- 1489

- 1490

- 1491

- 1492

- 1493

- 1494

- 1495

- 1496

- 1497

- 1498

- 1499

- 1500

- 1501

- 1502

- 1503

- 1504

- 1505

- 1506

- 1507

- 1508

- 1509

- 1510

- 1511

- 1512

- 1513

- 1514

- 1515

- 1516

- 1517

- 1518

- 1519

- 1520

- 1521

- 1522

- 1523

- 1524

- 1525

- 1526

- 1527

- 1528

- 1529

- 1530

- 1531

- 1532

- 1533

- 1534

- 1535

- 1536

- 1537

- 1538

- 1539

- 1540

- 1541

- 1542

- 1543

- 1544

- 1545

- 1546

- 1547

- 1548

- 1549

- 1550

- 1551

- 1552

- 1553

- 1554

- 1555

- 1556

- 1557

- 1558

- 1559

- 1560

- 1561

- 1562

- 1563

- 1564

- 1565

- 1566

- 1567

- 1568

- 1569

- 1570

- 1571

- 1572

- 1573

- 1574

- 1575

- 1576

- 1577

- 1578

- 1579

- 1580

- 1581

- 1582

- 1583

- 1584

- 1585

- 1586

- 1587

- 1588

- 1589

- 1590

- 1591

- 1592

- 1593

- 1594

- 1595

- 1596

- 1597

- 1598

- 1599

- 1600

- 1601

- 1602

- 1603

- 1604

- 1605

- 1606

- 1607

- 1608

- 1609

- 1610

- 1611

- 1612

- 1613

- 1614

- 1615

- 1616

- 1617

- 1618

- 1619

- 1620

- 1621

- 1622

- 1623

- 1624

- 1625

- 1626

- 1627

- 1628

- 1629

- 1630

- 1631

- 1632

- 1633

- 1634

- 1635

- 1636

- 1637

- 1638

- 1639

- 1640

- 1641

- 1642

- 1643

- 1644

- 1645

- 1646

- 1647

- 1648

- 1649

- 1650

- 1651

- 1652

- 1653

- 1654

- 1655

- 1656

- 1657

- 1658

- 1659

- 1660

- 1661

- 1662

- 1663

- 1664

- 1665

- 1666

- 1667

- 1668

- 1669

- 1670

- 1671

- 1672

- 1673

- 1674

- 1675

- 1676

- 1677

- 1678

- 1679

- 1680

- 1681

- 1682

- 1683

- 1684

- 1685

- 1686

- 1687

- 1688

- 1689

- 1690

- 1691

- 1692

- 1693

- 1694

- 1695

- 1696

- 1697

- 1698

- 1699

- 1700

- 1701

- 1702

- 1703

- 1704

- 1705

- 1706

- 1707

- 1708

- 1709

- 1710

- 1711

- 1712

- 1713

- 1714

- »